“You needed to know what it felt like.”

Devra Torres | Mar 8, 2016

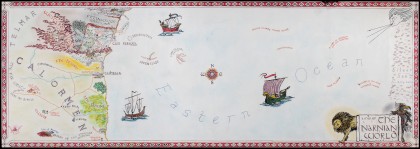

In one of the inexplicably less popular Chronicles of Narnia, The Horse and his Boy, The Tarkheena Aravis escapes her home at dead of night to avoid an arranged marriage with a repulsive and elderly suitor. She's drugged her maidservant so that she'll sleep through the escape, unconcerned about the beating the girl will get for her negligence.

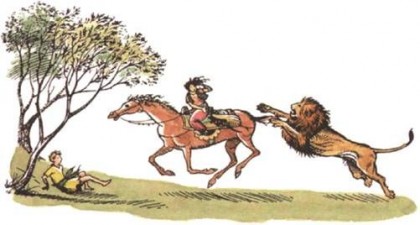

The first time Aravis meets Aslan, he chases her down, leaps up and claws her back, and then mysteriously turns and rushes away.

Later, when she gets to know him better, she asks him about this, and he tells her that the wounds match, stripe for stripe, the lashes the maidservant received. "You needed to know what it felt like," he explains.

I think there's a lot in that.

It's not that it explains the mystery of suffering. It doesn't clear up why bad things happen to good people: Aravis is not an especially good person; she's a spoiled princess who never wastes a thought on anybody of lower status unless pressed to do so (at least early in the story).

Nor do Aslan's words refer to bad things happening to bad people, as punishment. This kind of suffering is neither gratuitous nor retributive. It's meant to effect something that can't be accomplished any other way.

I'm writing this as we're trying to figure out what in the world God has in mind for us. We made a simple plan, and many months into it, our life is still an endless train of complications.  We thought we'd sell our house in Michigan, buy one in Maryland, and settle in. Instead we struggled to sell there, failed to buy here, had to move anyway, rented here, finally sold there, had a sale fall through here and are renting again. Now we're house-hunting and rental-hunting, since in two weeks cherry blossom season kicks in and somebody else has dibs on where we are now.

We thought we'd sell our house in Michigan, buy one in Maryland, and settle in. Instead we struggled to sell there, failed to buy here, had to move anyway, rented here, finally sold there, had a sale fall through here and are renting again. Now we're house-hunting and rental-hunting, since in two weeks cherry blossom season kicks in and somebody else has dibs on where we are now.

We're certainly not homeless; we're just temporarily between warm, spacious, comfortable dwellings. We're not refugees driven from our homeland (even if our landlord did seem disconcertingly happy to see us go). I would never, ever presume to compare the protracted inconvenience of our life to the tragedy of homelessness or forced emigration.

But whatever other purpose this ridiculous odyssey serves, maybe it's partly meant to give us just the tiniest hint of what it's like to be rootless, unstable, and uncertain. Before, I'd pray with the kids for homeless people and refugees. I'd try to explain that these people had all the usual human troubles (sickness, troubles with relatives, addictions, depression, anxiety, boredom) and then on top of that, the ground-shifting-under-your-feet feeling of being homeless or country-less. I was trying to cause them, and myself, to experience empathy, but without the inconvenience of shared experience. It wasn't really working.

But now we may be getting somewhere. t's just a fraction of the hardship. But maybe we needed to know what it felt like.