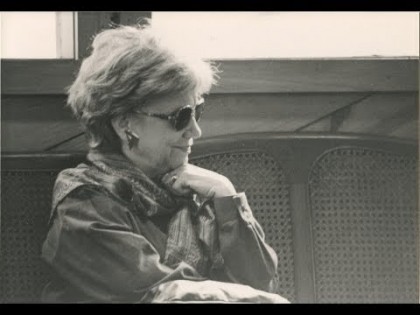

Dr. Louise, Personalist Extraordinaire

Devra Torres | Nov 23, 2015

The great Dr. Louise Cowan died a few days ago at the age of 98. She'd held chairs, founded institutions, written ground-breaking works of literary theory, and won awards and medals, but I knew her as my teacher at the Thomas More Institute of Liberal Arts and later at the International Academy of Philosophy.

Dr. Louise was a professor of literature, not philosophy, and I don't recall the word personalism ever passing her lips. She lived it, though.

Coasting through life on automatic pilot, running on inertia, following the crowd--these were thoroughly foreign to her. She could have pleaded some excellent excuses: near-blindness (originating in a long-ago thyroid problem); extreme old age (she continued teaching and public speaking into her nineties); caring for a husband who, in his own old age, no longer recognized her--but no, she spent her life delving into good things and showering them on her students, even the lazy and unappreciative ones (but more on that in a minute).

She didn't cut herself slack, either. Truth trumped everything, and literature was an authentic path to truth. I remember her saying, "You know, I've been teaching it this way for twenty-five years, but when I read it last night, I realized..." She encouraged us to shun going through the motions, too. If we'd worked all night on a paper and then realized our thesis didn't hold up, she told us, we should go ahead and insert a "not" in the first sentence. Nothing that smacked of fakery got by her.

In fact, in my two decades as a student the only teacher who ever walked out on a class was Dr. Louise. As soon as it became clear that none of us had read the assignment, she just--left. I remember it thirty years later: it taught me more than I could ever have learned from spending that class-hour trying to blend in with the furniture, distracted by fear that my laziness might be exposed. Next day she was back, casting more pearls before a less swinish audience.

But that only happened once, and maybe it only worked because, seeing the caliber of the one we were disrespecting, we were already a little ashamed of ourselves. What I remember about her was not strictness but graciousness, and the way her love for what she was doing could draw all kinds of previously invisible riches out of any day's reading.

I remember finishing my Madame Bovary assignment and thinking that here was a fairly entertaining (if depressing) romance novel, but I was stumped about its presence in the core curriculum. Dr. Louise had a way of reading a book out loud, though, that brought out everything it had to give, and it turned out that Madame Bovary was about the bankruptcy of romanticism, the rise of scientism, and other surprisingly meaty themes that had escaped my notice entirely.

Because she was so gracious and brilliant, she inspired a lot of imitation, and even unintentional mimicry. We wanted to be just like her. She always discouraged this, just as she'd discourage our admiringly chiming in with her opinions. Once when we were studying Crime and Punishment she threw out the idea that since an author creates a whole world, when we're assessing, say, Sonya's life of prostitution, we should do it in the context of that world, not according to the truth about intrinsic good and evil that would normally apply. As I remember it, we all sat there deferentially drinking this in, until she finally burst out, in that unfeigned Southern accent: "Well now, isn't ANYBODY going to argue with me?"

She had no tolerance for manipulative sentimentalism, but, being warmhearted, she was susceptible to it even while seeing through it. "What a terrible movie!" she'd exclaim, after a low-quality tearjerker--but in tears, because it had worked.

I could go on, but the best tribute any of us can pay her is to live as she taught us to live--not, of course, to imitate her, but to walk in the truths she showed to us.

Image of Dr. Louise Cowan courtesy of the Dallas Institute