Dr. Seuss: Personalist or Radical Individualist?

Devra Torres | Jul 15, 2012 | 3 cmts

When I was very, very little, my beloved grandparents, Nana and Uncle Lenny (his real name was Louis, and he did eventually resign himself to being “old enough to be a grandpa”) gave me and my sister Abby a delightful present, which I am about to criticize.

Now, to say I have nothing against Dr. Seuss would be an understatement. He was so central a part of the family Weltanschauung that when my sister Sarah’s teacher once instructed her to design a family crest, he was included. (So were Groucho Marx and a bagel, but my other sister, Simcha Fisher, tells it better here.)

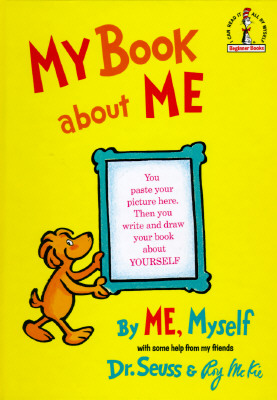

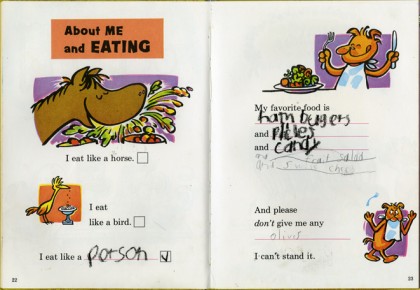

We loved My Book About Me, which was designed as a kind of treasury of memories by, for, and about the child. We didn’t notice anything strange about it, which was telling in itself. My mother did, though:

It had spaces to fill in your name and where you lived and what kind of house you lived in and your hair and eye color, and a lot about your personal preferences and likes and dislikes and individual style and all sorts of things like that.

I think he did include a little something about your family, but on the whole the emphasis was on those things that made the child unique and original--all sorts of things…. I was struck by how different such a book would have been if it had been written a hundred or maybe even just fifty years before. It would have started with the child's ancestry, and it would be a while before it got to anything else, because ancestry and family traditions and ways of bringing up children used to be considered the most essential part of the child's identity.

This led us both to reflect on the difference between personalism and individualism. I referred her to Dr. John Crosby’s very enlightening essay, "What we mean by Personalism" (from the “About” section of this blog). I was thinking especially of this part:

Our personalism has the effect of transforming the way we understand our social lives. We can no longer live in the social solidarity that was natural in earlier times. Parents no longer choose the profession and the spouse of their children;

they acknowledge that these are choices that can only be made by their children. We can no longer share the faith of our group merely out of loyalty to the group; as persons each of us acts in his or her own name in making basic commitments of one’s life. This is because persons are never mere parts in any social whole; we never exist in a social whole in the way in which organs and cells exist in a body. A human society is not a whole composed of parts, but rather, in the felicitous expression of Maritain, a whole composed of wholes.

So do we reject the idea that a large measure of our identity is bound up with the community and tradition into which we’re born? Are we disciples of Ayn Rand?

No. Emphatically not. Dr. Crosby explains:

It may seem to follow from this that personalism is just another species of individualism and is sure to bring severe social fragmentation in its wake. But most personalists have been very sensitive to the sterility of individualism. They have taken very seriously the interpersonal relations in which human persons live and move and have their being. The interiority of a person does not isolate a person from others, but rather opens him or her to others. Personalists refuse to think about social life only in terms of rights and of protection against intruders; they also think in terms of solidarity and co-responsibility. The personalism to which we are committed impels us to work towards a new kind of solidarity that is precisely based on the fact that each member, as person, is always more than a mere part of the community. For personalism the ideal of a communio personarum represents the only valid form of all deeper social life.

This, in turn, brings up a host of bigger-than-a-blogpost questions, especially those related to Bl. John Paul II’s fascinating ideas on how the person, as subject, only becomes who he is by opening himself to, and even giving himself to, other persons.

Solidarity and the communio personarum aren’t optional extras: they’re ineluctably central to what we are (our essence), how we’re made (our structure), and what we’re for (our telos).

Personalists acknowledge “those things that make the child”—or any of us—“unique and original,” without going to the extreme of treating him as an isolated being that has inexplicably emerged out of no particular history, family, tradition, or mediating institutions, put on earth by no one in particular to accomplish nothing in particular, or at least nothing beyond the self-contained unfolding of his own puny ego. We’re not single-mindedly focused on how “special” we all are. We’re not reacting against collectivism by imagining ourselves to be self-sufficient, or self-creating, bearing a single, sacred right--the right to be let alone.

So where does Dr. Seuss stand? Has he no personalist credentials?

On the contrary, the evidence supports our regarding My Book About Me as something of an aberration. Horton Hears a Who can plausibly be construed as an astute and rousingly incarnational defense of the dignity of the person, regardless of material mass. And The Grinch Who Stole Christmas is clearly an echo, albeit in an idiom proper to its genre, of the Wojtylean principle of the priority of being over having.

Comments (3)

Katie van Schaijik

Jul 16, 2012 4:00pm

Your post is reminding me of a theme of Ayaan Hirsi Ali's gripping book, Infidel, about her journey from a strict Muslim upbringing in Africa and Saudi Arabia to the west and to classical liberalism.

The book begins with a recitation about her ancestry, which was drilled into her by her grandmother when she was a small child. "This is who you are." The reader gets a vivid impression that this was a deeply held conviction, which is at once attractive and disturbing.

Her early life and sense of identity are entirely shaped and defined by her place in the family, the trible, the religion.

Her flight to the west (to escape an unwanted arranged marriage) was an act of monumental personal courage. She calls the day she did it—the day she took charge of her own existence, "My birthday as a person."

One also feels the tragedy of the fact that in order to "become a person" in that sense, she had to rebel against her family. It shouldn't be so!

We should find a way of being family and community without undercutting our vocation to be selves.

Devra Torres

Jul 17, 2012 10:30am

Yes, we need a "both...and" solution. We don't have to jettison one or the other. It's like when a child leaves home for college, or some other more separate existence, and then comes back and sees all the things about the way the family does things with new eyes, and has the freedom (at least in theory) to take a look at it all and decide what to keep and perpetuate, and what to reject or at least modify--moving beyond accepting traditional ways unreflectively and also rejecting them reflexively.

Gary Gibson

Jul 16, 2017 2:58pm

As always, very thought provoking . . .

thanks,

Gary Gibson