Examining Your Examination of Conscience

Devra Torres | Jul 19, 2013 | 2 cmts

I’ve been reading Jacques Philippe again. This brings on the urge to just string together Jacques Philippe quotes and call it a post, because, after all, who could say it better, or what is there to add?

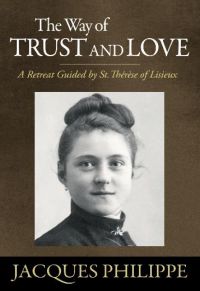

The book in question is called The Way of Trust and Love: a Retreat Guided by St. Therese of Lisieux (Scepter).

It’s perfect for people like me—and I suspect there are many—who suffer from the uneasy conviction that there must be more to the Little Flower than what we imagine, but who are too allergic to nineteenth-century religious prose to find out for sure.

This short paperback, as accessible as it is profound, will allow you to derive enormous amounts of spiritual nutrition from St. Therese without being troubled by any intolerance you may have built up against her genre. Think of it as gluten-free hagiography.

Much of the book centers around what she called “becoming little” (as in Christ’s command to become as little children). One mark of little children is their ability to get up, immediately and obliviously, after a fall and try again

(even if, like my own little children, they feel obliged to indulge in a certain quantity of pro forma weeping and wailing). Very little children are far more likely to be gleeful than brooding and introspective. Of course, they’re entirely self-centered--but they’re not morbidly self-absorbed. We grownup religious types, on the other hand—well, here’s the passage that especially struck me today:

There is a very subtle but common temptation in the spiritual life. With the excuse of wanting to be perfect, we seek to examine ourselves too much, to evaluate ourselves and measure our progress. The usual result is that a sort of discontent and permanent sadness slips into our lives, since we are never fully satisfied with ourselves.

This sadness is a pervasive feature of 21st-century life, at least in the “developed” world. On top of the burden of unremitting information about poverty and violence in places we hadn't realized existed, there's the epidemic of depression and anxiety.

We’re tempted to accept it as the “new normal,” rather than a sign that something’s deeply wrong, something that can be addressed.

Fr. Jacques continues:

Such an attitude causes us to center on ourselves when what we need to do is throw ourselves on God with unlimited trust. We’re more concerned about ourselves than about God….

Fr. Michel Esparza has elaborated at length on this insight, as we discussed here. And Fr. Jacques also wants us to be clear: we don’t have to choose between being morally upright, but depressed, or morally oblivious, but cheerful. Here’s how he puts it:

I don’t mean we shouldn’t examine our conscience: this is something we must do. But we should ensure that examination of conscience doesn’t degenerate into gazing gloomily at ourselves [emphasis mine]. The best way to enlighten our consciences and discern our real sins is to look at God, to take his Word as our mirror.

The idea of examining your conscience is interesting (especially to a personalist) for many reasons: it's not just about how to keep an accurate ledger of infractions: it intersects with questions like:

- How do I have a right relationship with myself?

- How am I supposed to reconcile my awfulness with my inalienable dignity?

- How can I attain self-knowledge without becoming an introspective bore?

Even if we retreat from the external evils of the world (either out of fear and isolationism or, more wholesomely, into nourishing, neomonastic micro-communities) we inevitably run into the internal evils: the ones we can’t escape by changing location, because “wherever you go, there you are.”

So it's worth considering how to face those evils, how to attack them without attacking yourself in the process.

I've heard lots of good advice over the years: do a daily exam, not just right before confession. Aim to cultivate virtues, not just eradicate vices. Include "What did I do right today?" not only "How did I fail to measure up again today?" Don't ask, "Am I doing all I can?" but "Am I doing what I'm supposed to be doing right now?" Don't be shocked by your past or apprehensive about your future. God is bigger than you think.

But, sure enough, Jacques Philippe says it better. It's less a question of technique, more a question of stepping back and identifying what we're really after:

The desire for perfection is a good thing in itself, but it can be ambiguous. What do we really want? We would like to be experienced, irreproachable, never make any mistakes, never fall, possess unfailing good judgment and unimpeachable virtue. Which is to say we would like to have no more need of forgiveness or mercy, no more need of God and his help. If at bottom our dream of perfection is to be able to manage without God, we are no longer on the path of the Gospel.

And here's another gem:

Living in the present moment means accepting the poverty in us: not insisting on going over and over the past or taking control of the future,but contenting ourselves with today. But this is very liberating: God does not dole out grace by a sort of profit-and-loss accounting of my past based on my good and bad actions. He gives me grace according to my faith today.

I could string together more quotes. But, better yet, read the book, and tell me, what are your favorite parts?

Comments (2)

James Barclay

Sep 17, 2013 3:35am

I haven't read the book, Devra, but I'll try and find it. I did see Jacque Arnaud's movie "Therese" and have listent to friends talk about her spirituality. (We have Catholic Worker Community, Sts.Francis and Therese C.W. here in Worcester, MA and Claire and Scott Shaeffer-Duffy have it. Claire has been very influenced by Therese). To me, Therese' spirituality was about a love so great for her fellow humankind that she could emanate it in a way that actually healed people. She healed them as she was herself being ill. This is particularly phenomenal in that I can find no other example except that of the healing of Longinus. I will say that I do not fully understand it. But I will say that out of one's suffering one can possibly help heal another person's suffering. And there are plenty of examples around. To me, this is one of the boons of personalism. Therese, of course, did this spiritually and by what we might think 'long distance'. but nevertheless, it is attributed to her. I am not a Catholic, So I might have missed something. I'll read.

Mary

Jul 20, 2017 4:13pm

I haven't read it either, but it does go along with what I have heard. Our path to holiness is in God's hands, and to give him glory, not us. I have recently been reading something about mustard seed evangelization. Part of the book is about what children teach us about God through the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd. One of the things is about God and our lives being mixed together like wine and water. Once they are together, how can you get them apart? Jesus is always with us, on our side, taking care of us. Therese once said to Jesus, I am your toy ball, you can play with me, or leave me in the yard. In the consecration to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, he says to us, give me your concerns, and take mine.