In Praise of Hypocrisy (No, Not Really)

Devra Torres | Aug 31, 2012 | 5 cmts

This quote was brought to my attention by my friend Jennifer, for whom I have enormous respect. We don’t agree much on politics,

but we do concur on the more important things. (Yes, there are more important things!).

I clicked on “like,” but something about the quote bothered me. It was hard to put my finger on.

It reminded me of St. Francis’ saying, “Preach always! When necessary, use words.”

Oh, wait. Turns out he never seems to have said that. But we all see the point: practice what you preach. If you don’t, then

- You a hypocrite, and therefore,

- You’re shooting yourself in the foot, because no one’s about to listen to a hypocrite.

So, sure, we can all agree: practice what you preach! Have some integrity! Don’t be all talk and no action! It’s bad for us as persons when we lack integrity, and it’s bad for the ones we’re trying to edify. It’s straight out of the Bible:

And clearly, haranguing people about your dead faith will neither bring it back to life nor inspire your harangue-ees to get religion.

But there’s a second, more questionable interpretation of the Cory Booker quote: that you’re not allowed to discuss religion unless and until you’re a perfect embodiment of your beliefs.

(This unfortunate idea pops up in parenting books, too: If you’ve ever tried drugs, you can’t advise your kids against smoking pot.

Or if you’ve ever fallen short of chastity, you can’t encourage your daughters to stay out of dark alleys with their boyfriends.)

To preach something you’ve ever failed, or are still failing, to practice—according to this interpretation--makes you a hypocrite. (It’s also an exceedingly handy copout: we’re all imperfect, ergo we’re all off the hook! No more initiating uncomfortable conversations about morality or religion—something most of us are quite powerfully inclined to avoid anyway.)

It’s this mistaken idea of hypocrisy I’d like to address.

The thing is, I’ve often—even life-changingly—been inspired by people who clearly had trouble practicing what they preached. My mother found the same thing: before her conversion to Catholicism, she was struck by the way every Catholic she ran into considered him- or herself a bad Catholic.

When I was newly married, too, I got some wonderful help from a woman who was smack in the middle of some awful marital conflict. And my friend Julia’s parents transmitted their faith effectively, in spite of their own history of drugs, instability, and occasional physical violence. While they were still struggling with these things, they were effective “preachers”—certainly not because of their defects, but because Julia observed that they were never self-deluding or arrogant about them. They overcame these vices, through a powerful mixture of grace and stubbornness, and attained a stable and happy marriage, family, and faith life.

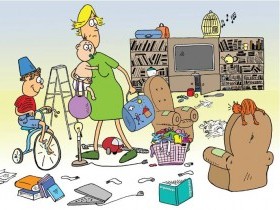

Here's a good description of hypocrisy that I heard once on the final day of a retreat. The rubber was about to meet the road: time to translate all those pious thoughts and noble resolutions that come so easy when you’re whisked away from moldering laundry and leaky syrup bottles to the company of pleasant grownups on their best behavior. Time to grit your teeth and face that most daunting hurdle of all: Being Nice to the People You Live With.

The speaker told us, Look: if you proclaim that from now on you’re not going to holler at your kids, but you’re secretly planning to do it the minute you get home—that’s hypocrisy.

But if you resolve that you’re not going to holler at your kids, and the minute you get home, you find the fruit flies have commandeered the kitchen, and you holler—that’s not hypocrisy. (It’s weakness—it’s not recommended—but it’s not hypocrisy.)

No one minds so much hearing about God and religion from someone who’s struggling to be good, isn’t there yet, and knows it. It’s the pretense, the arrogance, the self-righteousness—not so much the failure--that's the problem..

Now of course you have more credibility if you’re living your faith well. it’s appealing to see people manifest their love of God in “how they treat other people” and how they “love all God’s children.” Who could object?

But there’s also a kind of negative inspiration that can be even more effective. Nobody’s supposed to aim at providing that kind! But nor should we censor ourselves, submitting to a moratorium on religious talk until we’re all perfect specimens ourselves.

Comments (5)

Kate Whittaker Cousino

Aug 31, 2012 1:20pm

Yes!

Sooner or later, anyone who holds any standards at all will appear hypocritical, and the higher your standards are the more likely you are to fall short of them. The true hypocrite is not the woman or man who holds themselves to a standard which they find difficult or impossible to live up to, the true hypocrite has two entirely different sets of standards - one for others and one for themselves.

"For all have sinned and fall short of the Glory of God."

Michael Healy

Aug 31, 2012 4:56pm

Devra--Great post! If we could never discuss ethics without being perfect, we could just never discuss ethics--never point to the ideal, even if we don't reach it. But it is extremely important to point to the ideal, and keep in in view. Weakness and failure are simply not hypocrisy, they are just human. But so is striving after the ideal.

Jules van Schaijik

Aug 31, 2012 8:32pm

Nice and much needed explanation of the difference Devra. Thanks!

Scott Johnston

Aug 31, 2012 10:55pm

Excellent!

It strikes me that Catholics who strive to practice their faith seriously (i.e., they go to confession regularly) are least likely to fall into this. That's because every time they make a good confession, they are reminded of the reality of human weakness--especially their own--and how much they need grace to be transformed. A society without the sacrament of confession is even more susceptible to pride in its endless forms.

Devra Torres

Sep 1, 2012 7:04pm

Kate, you're right: it's not how high the standards are, but how many sets of them you have!

Michael, thank you! I remember studying ethics with Mark Roberts in college and he started out by explaining that his role as our ethics teacher was not the same as a claim to be a perfectly ethical person.

And thank you, Jules--especially in an election year, it's a subject that bears thinking about.

Scott, yes--confession is good for self-knowledge, and people find other ways, if they don't believe in the sacramental kind, to confess--from journaling to announcing things to strangers on the internet to all kinds of bizarre reality shows. Not that the grace of self-knowledge is given through this kind of pseudo-confession.