It’s Not My Fault!

Devra Torres | Jul 28, 2013 | 10 cmts

Occasionally, on my morning trek to the coffeepot, I encounter a small child standing next to, say, a little pile of broken glass and strawberry jam.

The child will immediately launch into a convoluted and highly implausible explanation of why the blame for the mess ought to be laid at the feet of some absent (or even fast-asleep) party.

The trouble with this is not just the blatant falsehood, even though, as both a philosopher and a mother, I take a keen interest in truth. It's also that the child so firmly believes that identifying the guilty party is the ultimate destination of his quest. Wiping up the sticky and hazardous mess and carrying on as a slightly wiser and more cautious five-year-old has not yet occurred to him.

Finding out whose fault it is, I have to explain, is not the same as fixing the problem.

Jacques Philippe contends (at least implicitly) that there’s not much difference between my five-year-old and many of us.

We understand that finger-pointing (at ourselves or someone else) is not our definitive goal, but in practice we tend to forget it. We have a natural desire, and even need, for meaning, as Victor Frankl explains so persuasively in Man’s Search for Meaning.

But sometimes that natural desire can get a little warped. In the face of misfortune, we're liable to run around in mental circles, frustrated and ineffective, asking (in Philippe's words):

- Why is this happening to me?

- What did I do to deserve this?

- What mistake did I make?

- How long will it go on?

- What’s the quickest way out?

- Is this the way it usually happens?

And, of course

- Whose fault is it?

It’s reasonable and useful to ask these questions. If you can figure out what you did wrong, you can resolve not to do it again. If you do identify the culprit, you can quit blaming yourself or some other innocent party. You can gain self-knowledge, and you can get at the truth.

All worthy goals.

But sometimes, Philippe points out, there is no answer. Or there is, but we won’t know it for another year, or ten, or twenty. Or we’re too close to the situation, or too original-sin-riddled, to see clearly.

In many cases, he says, the relevant question is not “Why?” but “What am I being called to do in response?” Within every hardship is some kind of call. Maybe to repent, maybe to pray for the culprit, maybe to leave the situation to God and abandon the illusion that I can achieve somebody else’s repentance or conversion.

Getting stalled at the finger-pointing step is a tragic mistake, because it gives evil the last word. When you’ve located the guilt in yourself or someone else and don't proceed to address the problem, discouragement or despair is probably going to follow. These, in a sense, are worse than the wrongdoing, because while any sin can be forgiven and wiped out,

despair prevents a person from seeking forgiveness and freedom. So evil wins—not because it’s more powerful than good, but because we fail to take the initiative and do something about the evil.

We feel like we’re being vanquished by evil, but we’re being vanquished by our own inaction.

It doesn’t even make much difference whether it's self-recrimination or accusation of someone else, as long as it ends there. The devil isn’t called The Accuser of the Brethren for nothing.

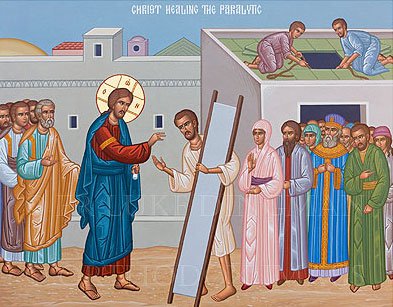

The Pharisees were accusers. They were rebuked not for their concern for the details of the Law but for ceaselessly poking and prodding other people’s souls in order to find fault. And notice what happens to them, and what can happen to us, if we get similarly sidetracked:

They become blind to the good that’s right under their noses.

We read with incredulity how they fail to marvel at marvels and wonder at wonders. Oddly heartless and devoid even of curiosity, they skip over the healing of terrible, long-drawn-out illnesses and hone in on the timing of the cures. They don’t stop to wonder at a lame man walking, but they do observe that he’s carrying his mat on the Sabbath.

In fact, violating the Sabbath is not some minor infraction: it was tantamount to lack of respect for God. But you get the sense that their professed reverence is just a pretext: they’re not honestly wondering if Jesus is “of God” or not; they’re just looking for an excuse.

Maybe we're not as transparently and passionately preocupied with finger-pointing as the Pharisees and my five-year-old.

Or maybe we are, and we just can't see it.

Comments (10)

Kate Whittaker Cousino

Jul 29, 2013 1:36pm

Well said. This resonates - of course, I have the same experience with my 5 year old fairly regularly!

Devra Torres

Jul 29, 2013 2:05pm

Yes, five-year-olds are very educational!

I want to write a continuation of this post, addressing some other points Philippe makes about how we persons have more power than we think, and how, both psychologically and supernaturally, we can only benefit by taking the initiative, asking the right questions, and not convincing ourselves that everything's out of our control.

Kate Whittaker Cousino

Jul 29, 2013 2:12pm

I would love to read that!

I've found a lot of peace lately in taking responsibility for those things I have power to effect, and relinquishing my sense of responsibility for those things that I cannot. Even if my actions don't always have the effects I might hope for, because there are other people or forces involved with their own influences, I can always act to become a more integrated, more whole (and, hopefully, holy) version of myself. To be *more* myself, as God created me to be.

Katie van Schaijik

Jul 30, 2013 9:38am

Dr. Peter's talk at our house a few years back, called "The Art of Loving Your Spouse, and what to do when you can't,"—or maybe it was the questions afterwards—mentioned the verse "first remove the log from your own eye". He pointed out how ready most of us are to grant the validity of the verse in cases where we have a log in our eye, but what about cases where we don't?

We all laughed.

He went on to propose that it's always the case, when we're speaking of another person's faults, that there is a log in our eye.

I've been thinking about it ever since, and agreeing with him more and more.

The very fact that we are concentrating on another person's faults and failing indicates that we are very far from moral maturity ourselves.

Increasingly, I am coming to appreciate that central to the moral life—at the heart of right relations—is the task of learning to attend to what is given to us to attend to, while laying off everything else.

We have to learn to mind our own business. It's hard.

Kate Whittaker Cousino

Jul 30, 2013 11:20am

Or, to put it in my mother's words (describing her own attitude as a child):

"It would be so easy for me to be good, if only everyone else was better!"

Much of the time, other's faults draw our attention because we imagine, and wish for, a world where being 'good' took much less effort, where our rough edges would never rub up against anyone else's and cause us pain. The problem with that is that we wind up expecting other people to take responsibility for our own sins (eg the child's cry, "but he MADE me mad!"), rather than take responsibility for them ourselves. Too often, we disguise this misdirection under a claim of responsibility for others, when it really is just meddling. Even in those cases where we are responsible for others (as a parent is for minor children), we err if we attempt to control behaviour (to usurp autonomy) rather than merely guide it and create boundaries around it.

Katie van Schaijik

Jul 30, 2013 11:30am

Another key reason we attend to other people's moral business is that it's easier than attending to our own. It's another form of "the grass is always greener". Other people's moral challenges look like a piece of cake from where we're standing.

Also, it gives us a feeling of superiority.

Rhett Segall

Jul 30, 2013 1:47pm

Apropos of fault finding is this Journal entry of Raissa Maritain:

“If we ought to be merciful and compassionate towards our neighbour, we ought to be so above all when we know his dominant fault. The first impulse is to bring all our severity to bear on it.but, on the contrary, it is on that we must concentrate all our charity; for it is a weakness which ought to be sacred to us for God alone can deal with it and cure it. These great defects of our brothers are like a nakedness we are not permitted to look at. But let each one of us bring his infirmities before the eyes of God, humbly imploring him to cure us. For this divine gaze may see all nakedness, moreover everything is naked before him, who heals and reclothes with light. August 16, 1917

Rhett Segall

Jul 30, 2013 1:51pm

Raissa's Journal

Katie van Schaijik

Jul 30, 2013 2:07pm

I love Raissa's Journal. One of my favorite lines:

"I'm suspended between heaven and earth by the mediocrity of my desires."

Devra Torres

Jul 30, 2013 10:59pm

Kate: Yes--"to become more myself"--that's exactly it. It's easy to get distracted.

Katie: Yes, the log-in-the-eye point reminds me of von Hildebrand's different kinds of "value blindness."

Rhett, I'll have to read Raisa's journal. I don't know how I got to be this old without doing that yet!