Martyrs and Migrants

Devra Torres | Mar 4, 2015

I just read one of those articles that throws off your whole writing schedule. I can't imagine addressing any other subject until I tell you about it.

The article in question is called Isis Boasted of These Christians’ Deaths. Here Are The Lives They Lived. I can't urge you strongly enough to read the whole thing (it's not long). The reporter traveled to Al Aour, home to 13 of the murdered Copts, and spoke to their families about them. In just a few words, their relatives painted a vivid picture of who these men were.

And there’s no stronger remedy against reducing people to mere symbols, or debating points, or generic sources of “inspiration” than getting to know them—even the slightest bit—as persons.

Especially when someone dies a horrifying martyr's death, it’s easy to skip straight over seeing him as a person to considering only his death and its meaning.

It’s funny that these relatives' accounts are so striking, because in the little details they mention there’s not much that’s unusual or spectacular. They loved their children. (“If I yelled at one of the kids he would get upset with me and would take the child and hug him,” says one widow.) They had strong faith. (One woman says her son's "faith gave him the courage to go to Libya in the face of danger.

'I have one God, he's the same here and there,' she remembers Yousef saying.") They were hard workers. (One family of five lived in a single room but the father worked so hard he managed to send his eldest daughter to college.)

And then there are the reports of the lone non-Christian from Chad who died as a martyr, sentencing himself with the words "Their God is my God."

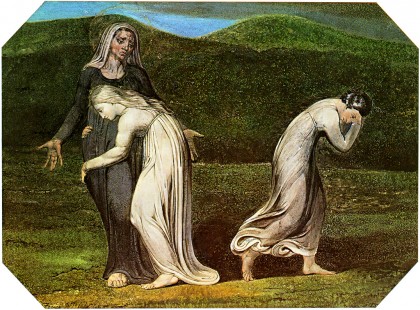

Straight out of the Book of Ruth, succinct as the story of the Good Thief.

And about those videos we discussed last week, whether they should be avoided like the plague or faced head-on, or something in between. The relatives of one man had the opportunity to see the martyrdom of their own son and brother on video.

Theresa refused to watch the video showing her son beheaded. But her other son says he made himself watch it.

"I saw that he had strength in his last moments," the 27-year-old man said, insisting that there was a heavenly light shining on his brother's face, even after he was decapitated. "And that consoled me."

For these people, the decision wasn't a theoretical matter with pros and cons to contemplate. There was no room for theoretical anything. They made their choice, and I'm certainly not about to second-guess them either way.

Pope Francis says we should give up indifference for Lent. When someone is beheaded for his faith, we’re in danger of becoming indifferent to him as a person: he becomes just one more newsfeed item--albeit the more somber kind--scrolling along in an endless parade of kittens and grandbabies and politicians. But what about all those people who don’t meet a violent and dramatic end but live out their lives laboring away in dangerous and uncomfortable places because their own countries can’t give them the means to feed their families?

Once as a student in Liechtenstein I needed to raise some money quickly for a trip, so found a job as a temp worker in a plastic factory. I’d get up before daybreak to catch the bus into Switzerland and then the train to the factory, where I’d work a twelve-hour shift, ride home, swallow some pain reliever, collapse, and do it again. I did this for all of ten days, and I was pretty impressed with myself, at first.

The work was strenuous and the hours were long, but that wasn't the shock. What got me was the way the bus stop at 5am was crowded with guest-workers already. It dawned on me that they were there every day, not just if they wanted to finance a whim. There were Poles, Serbs, Spaniards, Turks. They gave every indication of being people going about their everyday business.

"Indifference" didn't begin to describe it. I had been entirely oblivious.

And this was paradise compared to plenty of places. This factory, being Swiss, was spotless and well-ventilated. The lunch we'd buy across the street was succulent and abundant. It's not like I was stuck in a Cambodian garment factory. It's not like I was laboring in a country overrun by terrorists.

Giving up indifference can seem like an abstract thing--until you get to know the people you've been targeting. Reading and these martyrs' families' own words is a start.