Q & A with Jacques Philippe

Devra Torres | Nov 29, 2013 | 1 cmt

A recent gathering with Jacques Philippe ended with a question-and-answer session. One question especially caught my attention. I’m certain this participant spoke for large numbers of us. How, she wanted to know, are we supposed to reconcile “Accept your failures” with “Be perfect”?

This conundrum is a stumbling block to many—they’d like to take to heart the encouraging words of people like Fr. Jacques and Pope Francis, who insist that we can enjoy peace and an unshakeable interior freedom despite our weakness and moral failures. But just how do you do that, without shrugging off divine and moral law--in this case, a clear directive, from the lips of Christ Himself, to "be perfect"?

How can you have it both ways?

Let's begin by weeding out certain things that the commandment to "be perfect" doesn't mean.

First of all, failure to live up to our own image of who we’d like to be shouldn’t derail us. If we get despondent about our modest IQ, short legs, or tone deafness, our task is not to change the unchangeable, so as to be “perfect,” but to accept it, put it in perspective, and focus on what’s good about the unchosen aspects of who we are.

Second, of course, "be ye perfect" doesn't mean "be ye a perfectionist."

And third, in the quest to be "perfect," we need to separate out legitimate goals and ideals from those imposed on us by others, especially parents and admired (or intimidating) role modells. Some people are so close to us that their requirements echo in our heads as if they originated with us, or with God Himself.

Now, If our parents encouraged us to cultivate our God-given musical abilities,

or to pursue excellence in our daily math homework, that’s one thing. If, on the other hand, they made us feel, deep down, that we would always be a failure unless we achieved superstardom, that's quite another.

or to pursue excellence in our daily math homework, that’s one thing. If, on the other hand, they made us feel, deep down, that we would always be a failure unless we achieved superstardom, that's quite another.

Finding the line between urging on children insufficiently and

excessively, and avoiding pushing them in a counterproductive way, is one of the trickier aspects of raising them. And for the children themselves, sorting through the legitimate from the bogus demands can be a complicated, long-drawn-out process. But one thing is clear: “be perfect” doesn’t mean meeting every unreasonable expectation that's ever been foisted upon you.

But what about demands that do come straight from God, and from the moral law?

What if the failures that nag at us, getting in the way of our peace and freedom, are not failures to meet unrealistic expectations, imposed from without, by parties who had no right do so? What if they're real, legitimate directives like, say, “Cease to do evil; learn to do good!” What could reconciling ourselves to our sinfulness mean but settling for failure, choosing feel-good-ism over objective truth?

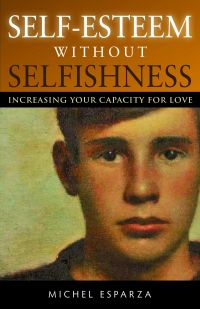

Michel Esparza has a lot to say about this in Self-Esteem without Selfishness, now available in English (as I’ve mentioned a time or twenty), and you can read about it here. But Fr. Philippe had some helpful thoughts to add.

First, he said, we need to consider context: God doesn’t just order us: “Be perfect” but rather “Be holy because I am holy” and “Be merciful as your Father is merciful.” This puts the whole question into the context of a relation between persons. He, our model, is a benevolent Father who treats us with the goodness He demands of us.

Also, He is speaking of the "perfection of love," not an external perfection, a mere "irreproachable way of living." He’s not talking about conformity to an external ideal but about "putting everything we have at the service of love."

Fair enough, you might say. But we fail at that, too. What’s so positive about such failure, and how are we supposed to be peaceful, joyful, and free in the face of our own malice and selfishness?

My weakness, Fr. Jacque replies, can help me to understand others better and thus make me more perfect in love. Yes, "there’s a bad way of accepting our own weaknesses [laziness, mediocrity], but also a good way." Weaknesses are not opposed to love—just the opposite. Weaknesses are positive "insofar as they become an opening"—an openness to God, to His forgiveness, and also to others, from whom I can accept help, for example. "Weaknesses force us to leave behind the logic of power, of possessing, of trying to be all-knowing."

As Fr. Franacis J. ("Rocky") Hoffman of Relevant Radio once put it, eventually our weaknesses can bring us—sooner or later—to the point of throwing up our hands and blurting out, "OK, fine! I’m convinced! I admit it! I can’t do anything at all without You!"

That’s when God looks down, breathes a sigh of relief, and says, “OK, good! NOW I can do something with you!”

Fr. Jacques had much more to say than I can recount. You can hear every talk here at the website of Christ the King parish in Ann Arbor.

Comments (1)

Katie van Schaijik

Nov 30, 2013 1:38pm

"Weaknesses force us to leave behind the logic of power..."

That's what it's all about: abandoning the logic of power, and absorbing the logic of love.

It's a hard lesson to learn. We so hate to admit impotence. We're so attached to power. We're so used to admiring it, and to despising weakness—in others and in ourselves.