Ralph Martin and the Language of Personal Decision

Devra Torres | May 15, 2015 | 6 cmts

In keeping with our outrageously inefficient lifestyle, this month the Torreses travelled some 800 miles to Warner, NH, to hear a talk by Dr. Ralph Martin of our home parish in Ann Arbor. (Actually the trip made some sense, since our son was graduating from Northeast Catholic College in Warner, and Ralph just happened to be the commencement speaker.)

My ears perked up early on. Ralph spoke of “the language of personal decision” which the Church has been using so insistently lately--especially since the pontificate of St. John Paul II.

“What does that sound like?” he inquired. “What does it remind you of?”

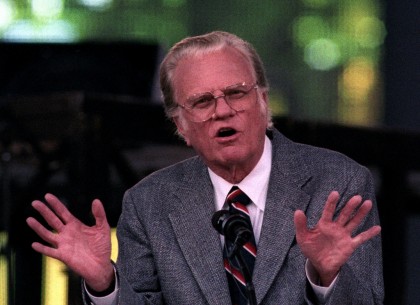

To some, he suggested, it might be reminiscent of Billy Graham, the world-famous 20th-century Protestant evangelist

After all, for a long time the Evangelicals seemed to have cornered the market on this kind of talk, with their insistence on the way a person's eternal destiny hinged on “accepting Jesus Christ as your personal Lord and Savior.”

There are problems with the formulation, of course--like the way it ignores the corporate aspect of the Church, and the fuzziness about exactly what "personal" might mean. But there’s a lot that's worth unpacking in such language, as I’ve written here.

Why is personal decision so important all of a sudden? For one thing, the times when a practicing Christian could cozily blend into the woodwork are fast departing.

In the days that are coming, Ralph pointed out, it will be hard to hang on if there’s been no personal decision on your part. You sure don’t "drift into the Kingdom of God by going along with the culture.” One way or another, “Who do you say that I am?” will be addressed to each of us, and there won't be any room left for what you might call unintentional discipleship. “The Kingdom of God suffers violence,” says Matthew in his Gospel, “and the violent bear it away.”

This is a mysterious verse, and Ralph offered a new (to me) interpretation. It could mean “the violence of conversion.” Real conversion—even if it takes a gradual, undramatic form in a particular person’s life--doesn’t just happen to you without your say-so.

The language of personal decision comes up in the matter of mercy, too. The Year of Mercy is coming up, the time of mercy is now, as John Paul and Sister Faustina kept saying. But even something as gentle and kindly as mercy requires a personal response. “Every time Jesus extends mercy, He asks for a response of faith, repentance, conversion,” Ralph pointed out.

Of course, persons have been making decisions for as long as there have been persons. But there's been a tendency to downplay their importance, or even confuse an insistence on legitimate personal autonomy with arrogance or stubbornness, or with a relativistic mushy-mindedness.

Alice von Hildebrand makes a key distinction that’s stuck with me all these years: between passivity and receptivity. The human person is a really odd creature: gifted with freedom and self-possession, the capacity to act in his own name. And yet his most significant actions involve being receptive to God—not passive, but receptive.

There’s a balancing act here that I don’t fully understand, and it’s at the heart of personalism. To take our own subjectivity seriously, to be the protagonists, and not the spectators, of our own lives, we have to really act, really decide. The formerly prevalent way of talking—what you could call a “language of instrumentality”—included a lot of references to being God's “tools” or “instruments,” about being “molded” into His image. There was truth to that, too--I'm not setting myself up as wiser than all the saints and theologians who've talked that way over the millennia. The potter and the clay is straight out of Scripture.

But it can be very misleading, blurring the distinction between person and thing, subject and object, free being and machine. Katie has talked about this (and sparked a lively discussion) in her post entitled “Our decisions belong to us; we are responsible for them.”

So you don’t have to be Billy Graham to speak the language of personal decision. But then, the point is not what kind of language we speak, but what kind of persons we are.

Comments (6)

Gary Gibson

May 16, 2015 9:26am

Thanks, Devra. I have known Ralph Martin for some 45 years both personally and through his books, teachings, articles, and talks. It is helpful to me to hear someone else comment on his insights, since I may miss many of them, left to my own devices. Ralph is one of those people who can write well AND preach passionately. He not only inspires and informs, he fire me up! I know he became a personal friend of Pope St John Paul II, who insisted that Ralph contact his secretary anytime he was in Rome (to have dinner with the pope!). One time Ralph decided he might be overbooked in Rome and tried to skip dinner with the pope. The pope's secretary called Ralph directly and said "We know you are here. When can you come here for dinner." So he has his fans in high places. Even in some jaded European ecclesiastic circles, Ralph is known as "the American who still believes in Hell and the devil". He has had an enormous impact on the American Church and for me personally.

Katie van Schaijik

May 16, 2015 10:33am

I agree with Ralph that no one drifts into heaven by going along with an increasingly secularized culture.

On the other hand, (and without assuming that Ralph would disagree) we can, I think, move toward salvation without making a conscious decision for Christ.

We do it every time we make free and responsible choice for good; every time we act conscientiously.

I think, in a way, we can even be moving to closer to God at the moment we think we are rejecting him. This happens, for instance, when our idea of God is skewed by bad experience. If we grew up in an abusive family, say, where religion goes hand in hand with control and manipulation, then choosing to walk away toward health and wholeness might be an indispensable step toward finding our true selves, i.e., our self in right relation to God—though it may take years.

I make the point because sometimes in our evangelical zeal, we put pressure on people to "make a decision for Christ" who are not yet able to make that decision in an authentic human way, and we end up pushing them back rather than welcoming them in.

Gary Gibson

May 16, 2015 12:28pm

Absolutely, Katie. What makes the arguments of C. S. Lewis so potent are his rigorous training in logic AND his absolute rejection of the concept of God as a young man. By running away from inaccurate notions of God, he was moving closer to Him.

Devra Torres

May 21, 2015 10:19am

Gary, yes, one of the treats of belonging to this parish is how much we get to hear Ralph.

Katie, it's true--in fact, it's ironic that in the name of "personal decision" people are often pressured to profess that they've made one. A decision made under pressure really can't be called "personal" or even a real "decision." Then people are put in a position where they've supposedly committed themselves to live a certain way, and they feel guilt if they fail to do so, when in reality it wasn't really a decision in the first place--or it wasn't really theirs. In the Community Bible Chapel, when I was a kid, we'd have "altar calls," with people coming up to the altar in the view of the whole congregation and making a "personal decision" for Jesus. It's not that these can't be genuine. Lots of them are, and lots of them are the beginning of a genuinely new life. But the risk of pressure and pseudo-decisions is high.

Devra Torres

May 21, 2015 10:20am

Sometimes, too, by "personal" people don't really mean "freely chosen by the person" so much as they mean "intensely felt," and then when the feeling dissipates the person is left wondering if it was all just a fraud or deception.

Jules van Schaijik

May 21, 2015 6:03pm

Good point Devra. I hadn't thought of that.