Von Hildebrand’s joy in truth

Katie van Schaijik | Nov 17, 2011 | 2 cmts

On Tuesday Jules and I drove in to New York City for a Dietrich von Hildebrand Legacy Project event. It featured a talk by his widow, Alice, on his life-long fight against relativism: "Relativism in the intellectual sphere and relativism in the moral sphere."

On Tuesday Jules and I drove in to New York City for a Dietrich von Hildebrand Legacy Project event. It featured a talk by his widow, Alice, on his life-long fight against relativism: "Relativism in the intellectual sphere and relativism in the moral sphere."

She spoke of her husband's dramatic and often very difficult life. "When I met him, he was a refugee. He had lost everything, because of his fight against Naziism, and yet, he radiated joy." His joy came from his faith, and his total confidence that "truth would win in the end."

She contrasted this joy with the kind of shallow optimism that brushes problems aside, that doesn't take evil seriously, that imagines that everything's basically okay. Von Hildebrand was far from being an optimist of this kind. On the contrary, his rootedness in Truth, his keen philosophical perceptiveness, his almost extreme sensitivity to error and wrong, and his total dedication to moral and religious values gave him extraordinary insight and prescience when it came to threats--threats to the dignity of the person or to the teachings of the Church. About our earthly prospects, he was under no illusions. Any yet, so potent was his joy and his hope in God that it drew many of his friends and associates into the Catholic faith.

We could use some more of that these days, couldn't we?

John Henry Crosby founded the Legacy Project with his father John F. Crosby. Madeleine Stebbins, widow of Lyman Stebbins, who founded Catholics United for the Faith, has been Alice von HIldebrand's closest friend for more than 60 years. [I'm sorry abou the poor quality of the photos! I don't understand cameras.]

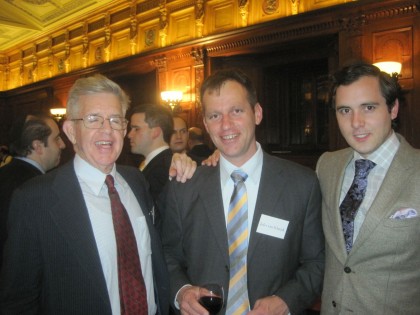

Here is a photo of Jules with Dr. Crosby and Gregory Woodward of the Raskob Foundation.

Here is a photo of Jules with Dr. Crosby and Gregory Woodward of the Raskob Foundation.

Comments (2)

Teresa Manidis

Nov 19, 2011 6:19pm

In researching the Second World War for my latest novel, I was struck by the very vivid perception the everyday soldier (or medic or front-line nurse) had of evil, tangible evil in their world. Seeing, first-hand, the atrocities perpetrated with regularity (the Bataan Death March, the deliberate bombing of hospitals and relief ships) heightened their awareness of both the reality of evil and the absurdity of relativism. When front-line Army female nurses made it to Dachau, for example, the prisoners were so emaciated that 50% of them died, even after receiving medical attention and the the last of the nurses rations. I've seen the data tables (who wrote and kept these records?) of the body weight upon capture and the body weight upon liberation of Navy nurses in the infamous Santo Tomas internment camp in Manila - 150lbs upon capture in 1941, 75 pounds by the summer of '45. To shrug today and say, go ahead-start-a-riot-burn-a-flag-burn-a-book-what's-it-to-me is cowardly in that we both hide our heads in the sand to the reality of true evil in our midst, and that we dishonor those who went (so very resolutely) before us. We are all connected. Tua res agitur

Katie van Schaijik

Nov 21, 2011 9:57pm

I agree that a general unseriousness about evil is one of the worst effects of "the dictatorship of relativism" we're experiencing today. Moral choices are reduced to lifestyle choices, without any sense or regard for the moral consequence for self and others. "Hey, whatever. Not my thing, but cool for you."

Even those of us who are (generally) clear about right and wrong find it very difficult to stand up for the former and against the latter in any open or public way.