The Wide-Awake Life

Devra Torres | Nov 10, 2013 | 3 cmts

I fully expected to spend this decade in a state of bitterly nostalgic melancholy. I had planned to squander it sitting helplessly by as my babies all got older, lamenting my inability to make them stop.

I’ve been happily surprised to find it hasn’t been like that at all (or only occasionally).

Maybe I speak too soon: my youngest is only five, still happy to sit on my lap and listen to “Big Y, little y, yawning yellow yak. Young Yolanda Yorgensen is yelling on his back.” I reserve the right to eat my words when the day comes that he’s too cool for such things.

But I find myself unexpectedly content to be enjoying my eight children right now, precisely at their present ages. It’s not just that caring for older children is easier: in some ways it’s much, much harder. I think this unlooked-for contentedness is pure grace, and I think it has implications that go beyond the wellbeing of one aging mama.

The key is an idea I’ve run into in a few different places—Jacques Philippe’s Interior Freedom

and de Cassaude’s Abandonment to Divine Providence,

for two. It’s this: human persons have the power to consent wholeheartedly—almost to choose—something we didn’t choose.

This is not the same as resignation. It’s not being stoical or forbearing or longsuffering. It’s something far more realistic—though by “realistic” I don’t mean that we bow reluctantly to unpalatable realities, but that we become able to perceive and respond to realities we would otherwise miss.

A mother pining for her child’s babyhood will be in no condition to relish, or even notice, the charm of who he is now. She’ll also be in no state to do and be what she's called to do and be for him now.

There’s a broader application: we can’t choose the time we’re born into. We can’t choose the present state of the Church and the world. We can choose our stance and our actions, though.

I hope I can put my finger on what I’m trying to say here. I don’t just mean it’s nice to accentuate the positive. I don’t mean we should feel good, or pretend to feel good, about the current glorification of sterility or consumerism or death. I certainly don't mean we should close our eyes to unpleasantness and evil.

I do mean that if Providence is real, then it’s no accident that we’re born when we’re born, into the middle of the particular historical mess where we find ourselves.

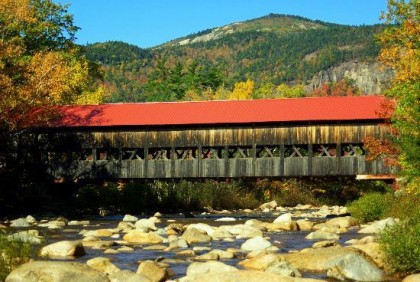

I mean that it’s in our power to choose to see and respond to the good, that whatever call the present moment contains for us, it’s never just the call to lament that it’s not some other moment. You might as well see the White Mountains

as a failed attempt at Alps,

or a folk song as an unsuccessful imitation of an opera. Or your teenager as a inferior version of your newborn.

It’s not that all historical epochs are equal, of course. Some times are evil times. But so much of the evil is noisy and obvious, and so much of the good is invisible and mysterious. If you’re fixated on the corruption and the danger, you’ll miss the good altogether, and you'll think you're being realistic.

The idea is not just to be resigned to reality, but to consent to the present moment as a call, straight from the mouth of the Creator, to be really present in the present, to be fully awake and responsive. We're called to relish what's good and throw ourselves into the adventure of overcoming what's evil.

Read Philippe and de Caussade. They say it better than I do. And if you want something really realistic, go to Tolkein, even though people call his genre "fantasy."

The world is indeed full of peril and in it there are many dark places. But still there is much that is fair. And though in all lands, love is now mingled with grief, it still grows, perhaps, the greater.

Comments (3)

Katie van Schaijik

Nov 11, 2013 7:28am

Devra, you remind me of something Archbishop Chaput said during election season: "We don't know what kind of America we're going to be living in, but we do know it will be the America God has chosen for us."

And like you, I feel like I've been learning a lot lately about living in reality rather than in illusion—whether the illusions of nostalgia or a fantasy future, when I won't be weighed down by my current responsibilities.

It's a key to personal maturity, isn't it?

Devra Torres

Nov 11, 2013 9:52pm

Yes: I think we human beings are a lot happier when we throw ourselves wholeheartedly into the sacrament of the present moment than when we limit ourselves to resignation to duty.

Jacques Philippe distinguishes (in Interior Freedom) between rebellion, resignation, and consent (to present reality). Rebellion against evil is good, but not a sufficient response. Rebellion against reality, as in a refusal to "walk in the truth," is not even a good transient response. Resignation means that at least you're in tune with the "resistance" of reality, but it's not the goal, either. Consent doesn't mean acceptance or tolerance of evil, but it implies trust that God can bring good out of it, hope that evil will not get the last word, and love of God. This faith, hope, and love, he says, can unleash the power of goodness in a way that mere optimism can't. Rebellion is sterile, and resignation saps us of energy. Consent is the way out: it allows us to be both realistic and effective.

Katie van Schaijik

Nov 12, 2013 3:43am

If I were home and had it handy, I would cite some beautiful lines from Raissa Maritain's Journal, where she speaks of the way we can turn unasked for and unwanted suffering into a gift by making it voluntary, that is to say, by choosing with our will to suffer it for love.