The Person She Used to Be?

Devra Torres | Apr 12, 2017

Stranded at a library the other day (not complaining!), I ran into a book by one John Zeisel called I'm Still Here: A new philosophy of Alzheimer's care. I've only read the first 40 pages or so, but he seems to avoid the kind of happy talk that flies in the face of reality. He doesn't pretend the disease is curable, or easy, or really positive in any way. But he does make two important points.

First, some troubles that we think of as Alzheimer's symptoms are actually avoidable side effects. For example, if a person wanders because she's at loose ends, or becomes agitated because of some unmet need, that's not a direct symptom of the disease, It can, at least sometimes, be avoided.

He also points out that although Alzheimers cannot be cured, it can be treated. What sense does that make? If there's no hope of a cure, why bother with treatment?

Well, for one thing, some treatments can delay the progress of the disease. I remember my mother saying that she'd hate that, and I'd probably feel the same way. But think of it this way, Zeisel says: at a certain age, a delay is as good as a cure--in fact, it's the same thing. If you can delay the worst of Alzheimers until, to put it bluntly, the patient dies of something else, you haven't just postponed the worst; you've escaped it.

He has other advice, too. For example, asking, "Do you know who I am?" can lead to confusion and embarrassment: the patient 1) may know perfectly well who the person is but not be able to pluck the name from her memory on command, or 2) she may not recognize the person at all and wonder why she's expected to, or 3) she may not remember the person but may sense that she's supposed to--also distressing and embarrassing. This could all be avoided by simply saying, "Hi, I'm Devra, and I'm happy to see you!" or some such thing. There's no need to quiz her.

This is not theoretical for me. My mother took care of her Alzheimer's-afflicted mother, and now she has it herself. Last time I talked to her, before hanging up, I said, "I love you, Ima," and she replied, "I love you, too, honey--what's left of me."

I tried to tell her that even if she didn't remember, and no matter how confused she was now, I knew there was more of her than what was "left" now, that I had known her for 52 years and remembered lots of things we did together, things she taught me, all kinds of things. She was in this condition now, but she was still a person. I have no idea if it helped, even for a minute.

Long, long ago, when I knew nothing about anything, I wrote a master's thesis on Self-Possession and Temporality in the Human Person. Boy, was it theoretical--a fascinating mind game, trying to tease out in virtue of what, exactly, we dare claim that we're the same person no matter our stage of development, degree of impairment, all the inevitable changes in body, outlook, personality.... I was 25 years old and had no skin in the game, nor could I imagine ever having any.

Now it's a practical matter. A relative who knew my mother long ago sent her condolences, expressing admiration and affection for "the person your mom used to be." I know what she meant. It feels that way to me, too: even though she's still there, I miss her. But I don't believe she's no longer a person, or that she's turned into somebody else. What's happened, maybe, is that she's no longer, or just barely, accessible to us now. Maybe even to herself. I think I would believe this if I didn't believe in an afterlife and the immortal soul, but maybe not. It's hard to say. And I know as she loses more and more of her faculties, it will seem more plausible that she's literally "no longer herself."

I want to end on a hopeful note, though, so here's some positive anecdotal evidence I can offer. My friend Wendy's grandmother had Alzheimer's. She was apparently a difficult and bitter person who'd had some awful experience in her youth which had made her that way. When she got dementia, in her mind, she went back to that youth: if you'd ask her how old she was, she'd give a younger and younger age each time. Eventually she got down to the age she was before the traumatizing event took place--and she lost all the bitterness. She became sweet and easy to get along with--the way she must have been before Wendy even knew her.

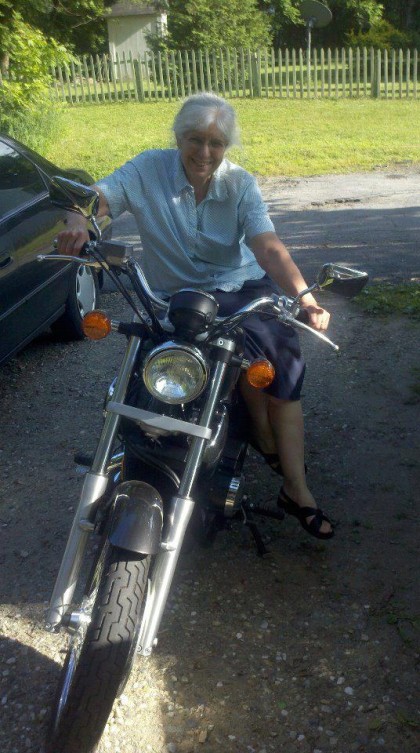

Something similar happened to my grandmother. She was a visiting nurse in Brooklyn for years and had an acute awareness of all the accidents and diseases that we oblivious grandchildren were risking at every turn. She was a worrier. But when she got Alzheimer's, that side of her personality vanished. She kept the affection and concern for everybody's wellbeing, but the worry somehow fell away.

Anyway, I've ordered Zeisel's book so I can read the rest of it, and if it's any good, I'll have more to say next time.