Beyond God as Errand Boy

Devra Torres | May 26, 2013

I’m reading a new book by Fr. Michel Esparza (author of Self-Esteem without Selfishness). The title translates as “In Tune with Christ.”

(Unfortunately, it’s not in English yet, but once I’m done with my current editing projects maybe I can start scheming to translate Sintonía. In the meantime, keep an eye out for Encountering Christ

and Pope Francis: Keys to his Thought, both from Scepter.)

and Pope Francis: Keys to his Thought, both from Scepter.)

Fr. Michel has a way of zeroing in on the commonest misconceptions with the most far-reaching implications, and then clearing them up—or at least throwing brand-new light on the things we say we believe.

He did it with self-esteem and self-love, and he does it here with certain habits well-meaning people fall into in their dealings with God.

He illustrates the problem by recounting how a priest friend of his once asked a large group of “exemplary Catholics” how they responded when they suffered some setback or contradiction---or, if they were taking on some voluntary sacrifice, why they did this.

Inevitably, the reply was: “I offer it up to God.”

He pressed on: “And what do you gain by that?”

Various answers followed. They offered it for some concrete intention: a child they were worried about, the physical or spiritual healing of some friend or relative, or to become a better person. Some expressed the hope that “the Lord would make it up to them” when they got to heaven.

He continued: “And what else?”

The answers petered out.

Conspicuously absent was any sense of empathy with Jesus Himself—any hint that these well-intentioned people were putting themselves in His shoes (or, in the more expressive Spanish idiom, "in His skin"). There was no apparent interest in whether these sacrifices gave Him any pleasure or consolation.

Fr. Michel continues:

This, unfortunately, is something very common. Right after the “I offer you” comes the “for....” One gives the Lord some gift but immediately adds a concrete intention. Without any ill will, one ends up treating Jesus as a simple intermediary, an “errand boy.”

Or one acts like a customer depositing a certain amount of money in the bank, entrusting the teller on duty with transferring it to the account of some debtor or benefactor.

He clarifies that there’s nothing wrong with the wish to be helped or to benefit others. Since God is merciful, He's happy to see us asking for His aid or concerned for others’ welfare.

But where does all this obliviousness to Christ's response come from?

I think it’s the convergence of two kinds of confusion:

1. About the hypostatic union: It’s authoritatively defined that Christ is, in St. Anselm’s words, “perfect God and perfect man,” and Scripture clearly affirms that He’s “like us in all things but sin.” Still, that leaves room for plenty of confusion about what a “perfect man” would look like. “Like us in all things but sin” seems pretty straightforward, too, until you realize that in us, sin isn’t roped off in quarantine but colors all our faculties. It darkens the intellect and weakens the will—but it also contaminates the affections. Thus, affections as we experience them can come mixed up with pride, insecurity, egotism, and other unsavory ingredients. This can make it hard for us to grasp that a perfect man would have affections at all. It's even more difficult to understand how an unchanging, eternal, spiritual being could be subject to the vagaries of feelings.

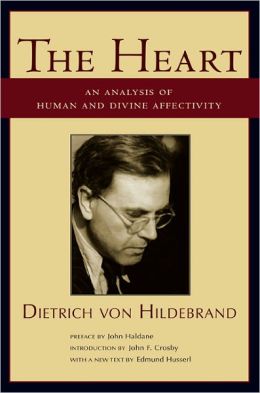

2. About the human heart: For a long, long time, what Dietrich von Hildebrand calls man's "affective center" has been reduced to a parody of itself: the seat of superficial, irrational, matter-dependent sentiments. Some have embraced sentimentalism, setting it up against rationality and unabashedly preferring what they call the heart to what they call the head.

Others grasp clearly that love is not “just a feeling,” and that affections and passion, no matter how intense, don’t cancel out the commandments. They’re keenly aware of how easily superficial sentiment can lead us away from truth. In fact, they either think that feelings inevitably mislead (in which case they’re dangerous) or that, at best, they can ease our compliance with truth by influencing our will. If God is perfect, and Christ is God, they reason, then Christ is clearly beyond feelings.

The Scriptures are full of His unmistakeable declarations of love, but if we're conflating affectivity with sentimentalism or irrational passion, it's hard to know just what to make of that. If we've reduced love to an impassive, disinterested benevolence, we're missing the point just as thoroughly. We may still end up treating Him like an errand boy or a bank teller, instead of a Person.

Von Hildebrand goes a long way towards untangling such misunderstandings in his 1977 work, republished in 2007 by St. Augustine's Press.

Jules van Schaijik addresses the issue in the March 22nd personalism class. And Esparza, building on von Hildebrand, C. S. Lewis, and the theology of the Sacred Heart and the Divine Mercy, addresses it in both Self-Esteem Without Selfishness (as discussed here) and Sintonía con Cristo.

But the confusion is so deep and so longstanding that the conversation needs to continue.