I Actually Remember Rosa Parks

Michael Healy | Jan 16, 2012 | 18 cmts

One day this past week, after morning Mass, a friend and fellow professor from Franciscan University of Steubenville casually remarked that this year (2012) marked the 50th anniversary of the opening of Vatican Council II. I responded, “That’s horrible! Don’t tell me that!” He was a bit shocked until I told him it wasn’t Vatican II that was horrible, but the fact that I can remember it—first hand! I’ll turn 62 later this year. I didn’t want to be old enough to remember the 50th anniversary of anything!

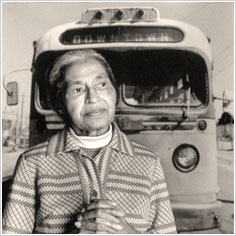

I immediately had two other thoughts. First, in 2 more years we’ll be subjected worldwide to the 50th anniversary of Beatlemania. I still recall vividly my sister and me sitting excitedly before the black and white TV in early ’64 to see the Beatles in their first appearances on the Ed Sullivan show. But, more seriously, remembering today’s holiday, my second thought was that I actually remember Rosa Parks refusing to move to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama in December, 1955 and the year-long boycott that followed with all its tension and trouble. Not that I remember all that clearly—I was 5 years old—but I was there and I remember what it was like in those days. My dad was stationed at Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Alabama from 1954 to late 1961 (two tours of duty, one at the Squadron Officers School, the other at the Air War College).

I immediately had two other thoughts. First, in 2 more years we’ll be subjected worldwide to the 50th anniversary of Beatlemania. I still recall vividly my sister and me sitting excitedly before the black and white TV in early ’64 to see the Beatles in their first appearances on the Ed Sullivan show. But, more seriously, remembering today’s holiday, my second thought was that I actually remember Rosa Parks refusing to move to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama in December, 1955 and the year-long boycott that followed with all its tension and trouble. Not that I remember all that clearly—I was 5 years old—but I was there and I remember what it was like in those days. My dad was stationed at Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Alabama from 1954 to late 1961 (two tours of duty, one at the Squadron Officers School, the other at the Air War College).

As things unfolded in the late ‘50’s and early ’60’s in Montgomery, I remember some of the upsets, the bombings, the threats, the tension, the federal troops sent in 1961 after trouble in response to the Freedom Riders. It was quite a shock to look out the window of our school bus on the way into Our Lady of Loretto elementary school in downtown Montgomery and see army jeeps with fully decked out, gun-totting soldiers in them. Was there war?

Now Maxwell Air Force base was actually like a little island of the north set down in the middle of the deep south. Segregation was forbidden on the base, including in the transportation system. Our parents educated my sister and me against prejudice and discrimination. Historically, as I discovered later, Rosa Parks actually got some major help and inspiration, before the bus troubles, from a married couple at Maxwell for whom she worked as a maid.

But, outside the confines of the air base, it was truly the world of To Kill a Mockingbird, and that’s the atmosphere I experienced from age 5 to 11. At times I found it strange and irrational. For instance, I noticed that in the back of the Montgomery Ward store (incidentally, Rosa Parks also worked there for a time), there were separate elevators, escalators, bathrooms, water fountains, etc., all marked “Colored Only.” Even by age 10, I wondered why people would spend all that money to duplicate all those services! It just seemed to be a complete waste. Especially now, looking back on it, in a capitalist society dedicated to profit, it amazes me how much money was spent just to maintain a social prejudice.

Sometimes, however, it wasn’t just strange but frightening. I remember, probably at age 7 or 8, being thirsty and approaching a water fountain for a drink. I didn’t think a thing about it, even though I could read the sign above the fountain. But just before I got a drink, a complete stranger grabbed me by the back of the collar, ripped me away, and said angrily, “Can’t you read, boy!” He pointed to the sign that said, of course, “Colored Only.” I had never been accosted by a complete stranger before in all my (admittedly short) life and I found it somewhat traumatic. I was scared. What would’ve happened if I’d taken a drink? Would I have died? Caught the cooties? Been arrested? Why would some passing stranger grab me like that, when my parents had not been concerned? Why did he think he had the right, or the obligation, to do that?

But this was the world outside the airbase. At school, though Catholic, the surrounding culture entered in by osmosis. When we as school kids chanted

eeny meeny miny moe,

catch a tiger by the toe,

if he hollers let him go,

eeny meeny miny moe,

sometimes we would substitute the “N” word and not think too much about it. We didn’t explicitly intend to be mean or disrespectful, much less hateful, but it was just part of the atmosphere—though we knew better that to sing it that way if any of the nuns were around, so we knew it wasn’t right. Again—talk about cultural osmosis!—even in Catholic school, when I was a “patrol boy” to help the younger kids across the street, we had special uniforms we could wear to school when we were on duty and special flags to stop the cars. Our uniforms, officially approved, were confederate army replicas (I still have a picture) and our flags were of the confederate battle flag. At the time, these things didn’t carry all the negative connotations they do now.

Now, my question today is why should we remember all this? We honor, of course, a great, and peaceful, black minister who helped to put an end to it. But, after all the ugliness, the riots, the hatred that followed in the ‘60’s and beyond, isn’t all this just a negative now? When we honor Martin Luther King aren’t we just reopening old wounds, causing more division, inciting needless resentments, driving people further apart for no good reason by remembering the injustices of a half a century ago? In remembering old injustices, in stoking hatreds, aren’t we encouraging hatred and retaliation now? Aren’t we just encouraging negative forms of “black power” and “black pride” at the expense of unity?

All these are dangers, of course, especially if unleashed in the political arena (perhaps for manipulative purposes), but I think there are deeper positive reasons—not involving politics—to recall the injustices of the past and those who struggled to eradicate them. I’m reminded of a memorial I visited in Paris, back in the summer of 1970, when I hoofed around Europe using Arthur Frommer’s Europe on $5 a Day (and you could actually it do in some areas). At the tip of an island in the Seine River is a memorial to the Jewish people persecuted by the Nazi’s. To enter, you walk down a long white marble staircase to an exhibit at the bottom—pictures, films, etc.—then you turn and have to climb up a corresponding long white staircase to get out. As you go up the white stairs with white walls and ceiling, you naturally look up to see how far away the exit is. And, in large black lettering above the exit are the simple words, “Pardonne, n’oublie pas.” That is, “Forgive, do not forget.” That’s the thought you can’t help but leave with after reviewing all the horrors.

And that is why we remember past injustices and those who heroically fought them. Not to inflame hatreds all over again, but to humbly and realistically acknowledge what we are capable of in how we treat other human beings and to remind ourselves of the need for forgiveness. We—any of us—are capable of great evils in dehumanizing other persons, or whole classes of persons. It has happened many times in the past and it can happen again. The treatments of blacks and Jews are most evident recent historical examples, but one could also speak of Stalin’s treatment of the kulaks, the treatment of the American Indians, of the Australian aborigines, of the handicapped, of women in history, of the unborn today. When a person is dehumanized, treated as a deficient human, as a non-human or sub-human, as vermin, as a parasite, as a disease, as a thing, as a non-person, as a waste-product, as an animal, etc., then we are all under assault in our most basic human dignity. (For a chilling study of such ways of speaking, see Dr. William Brennan’s Challenging the Language of the Culture of Death, at lifeissues.net. Also, the accompanying Table is especially illuminating, from his book Dehumanizing the Vulnerable, When Word Games Take Lives.)

Therefore, let us honor today a great civil rights leader of his time, and those associated with him, who helped reaffirm the dignity of each human being. We should not give in to prejudice and injustice just because it predominates in a culture. As Rosa Parks said, explaining her refusal to move to the back of the bus, “I was just tired of giving in.” She added, "When that white driver stepped back toward us, when he waved his hand and ordered us up and out of our seats, I felt a determination cover my body like a quilt on a winter night." This is how we have to be now about the denial of human rights to any class of people—including any ugliness lingering from the past prejudices, but especially I would submit, in our generation, concerning the war against the unborn.

Comments (18)

Katie van Schaijik

Jan 16, 2012 10:17am

"And that is why we remember past injustices and those who heroically fought them. Not to inflame hatreds all over again, but to humbly and realistically acknowledge what we are capable of in how we treat other human beings and to remind ourselves of the need for forgiveness."

I would add that it's equally important to remind ourselves not just of our need for forgiveness, but of our responsibility to make amends.

Ruan Kelly

Jan 16, 2012 12:03pm

"Forgive, do not forget"

I agree wholeheartedly with what both of you have said.

In regard the need to remember past injustices with humility and with the realisation of what humankind is capable of, As well as the responsibility to make amends.

I would like to add that this responsibility to make amends is sadly a distorted ideal in the contemporay world. Rather, so called "politically correct" langiuage is used that has very little to do with learning from past injustices or making amends. It is a convenient way society and indivduals have of not dealing with reality, specifically historical injustices. So called politically correct language becomes a way of depersonalizing concrete historical wrongs, glossing over them or acting like it is all in some foogy past. I fear this language is becoming a world-wide trend that can olny lead to a contiuation of prejudice, injustice and racism because it distorts and confuses the memory of past injustices and atrocities. Making it more difficult to learn from the past. And we all know what happens to those who fail to learn from past mistakes!

Michael Healy

Jan 16, 2012 3:44pm

Another example of the problem in Montgomery at the time that I forgot to include in the article is the following. One evening our family was just out for a drive around town as a pleasant pastime (this was before TV addiction set in), playing spelling games for fun and to build vocabulary. We sort of got lost and turned down an unknown street that was very poor and unkempt. It was basically a ghetto. However, as we soon discovered, it was a white ghetto and as such had to be completely separated from the neighboring black ghetto. How? Well as we drove down the block looking for a side road to turn on, instead we came up against what I can only describe as a minor version of the Berlin wall! The houses of the white ghetto ended and a 10 or 12 foot wall arose, cutting through the neighborhood and going right across the street, completely blocking it! On the other side was the black ghetto. I'm not a student or historian of the time period, but that's not the kind of thing I often see reported in history books, yet I saw it--and was really stunned.

Katie van Schaijik

Jan 17, 2012 8:43am

Michael, a propos of your point about being a bit chagrinned to discover that you remember things from 50 years ago, I bet you'll enjoy this essay by a priest on the problem of getting older and losing memory. I linked it in a post the other day. Here it is again, in case you missed it.

Laurence

Jan 17, 2012 12:50pm

I appreciate this discussion. The dripping sentimentality that is usually associated with the MLK holiday has, over time, made me kind of callous to the day, and forgetfull of what it stands for (just take a look at yesterday's and today's NYTimes Op-Eds to see what I mean). It also irks me a bit that we abrogated George Washington's holiday to give MLK's its proper place. Anyway, this is a refreshing visit back to the the process of realizing fundamental rights for all people, and is a celebration muhc bigger and more important than just Martin Luther King.

However, I'm left wondering via the comments. How do we make amends? Who owes amends to whom? When have we made enough amends? Is that ever possible?

It seems like ambiguous and/or gratuitous amending protracts the reconciliation process just as much as withholding forgiveness does on the other side.

Michael Healy

Jan 17, 2012 11:21pm

Katie,

The essay by the priest on memory as he got older was indeed interesting. When I think of it now, it leaves me with feelings that are sobering and even scary (as I recall); I just can't remember why.............

Laurence,

Yes, we do need to affirm the real value in these kinds of honorings and celebrations, and not let them slide into mere partisanship and divisiveness.

Also, "amends" doesn't have to mean "compensation" or "recompense" but can mean to alter, to replace, to substitute--so one way to offer amends is by replacing faulty attitudes and responses with genuine and true ones--and to spread the word.

Jules van Schaijik

Jan 19, 2012 11:41am

I finally had a few moments to read this beautiful post. Thanks! The only thing missing is the picture of you in your uniform.

About the amends issue. I think that truthfully remembering the past is itself a way of making (partial) amends. Victims of injustice want, perhaps more than anything else, the truth about their case to come out.

This is beautifully shown by Desmond Tutu, in his book No Future Without Forgiveness. He explains why, in order to move forward after the era of "apartheid", South Africa could not simply forget about the painful past and move on. To do so

He uses a play, Death and the Maiden, to illustrate the effect on a victim of the culprit's denial of his crime:

Laurence

Jan 19, 2012 12:04pm

Thanks for the responses about the right course for making amends. Certainly, remembering the past in a truthful manner is both very challenging and very very important.

But what if that is not enough for the offended party? They often have their own memories and opinions on the history--sometimes accurate and sometimes not--they may nnot always be satisfied with a truthful and just account.

Katie van Schaijik

Jan 19, 2012 12:13pm

Laurence, Jan. 19 at 12:04pm

But what if that is not enough for the offended party? They often have their own memories and opinions on the history--sometimes accurate and sometimes not--they may not always be satisfied with a truthful and just account.

I think maybe it's just here that we are challenged to forgive. The wrong is done and cannot be undone. In this life, for big injuries, there is possibility of just compensation. I am thinking, for instance, of the victims of clerical sex abuse. No truthful recognition of what they have undergone coupled with however many millions of dollars will give them back what was taken from them.

But if the truth about what they underwent is denied them--especially if it is denied by the one who inflicted the injury and then by others who believe him--the desire to forgive is complicated by the need to defend the truth of one's own experience and one's own dignity.

Jules van Schaijik

Jan 20, 2012 7:41am

Matt Leonard, Michael Healy's son in law, scanned and sent the picture I asked for above (#7). Thanks Matt! I love it.

http://www.thepersonalistproject.org/images/uploads/blog_entry_images/young_m_healy.jpg

(If Rick Santorum had a picture more like this, instead of that other one, his chances would be much improved.)

Michael Healy

Jan 20, 2012 5:17pm

Matt's in trouble now, for sending that picture.

Nonetheless, I have to admit, it is a picture of me in my prime! Shortly thereafter, I got big dark plastic horn-rimmed glasses and acne. I considered myself, consequently, as ugly and unattractive to girls. This caused no end of confidence problems in my teens.

But I still remember, at age 10, when this picture was taken, when a pretty little girl in my neighborhood on Maxwell AFB, used to come out every Sunday morning and wait in front of my house to see me come out all dressed up in a nice suit for Sunday mass (things were more formal then) just because she thought I was so handsome!

Until Maria, my wife, fell in love with me when I was 24, I always still felt somewhat ugly and unattractive.

Katie van Schaijik

Jan 20, 2012 5:25pm

It's a completely charming picture! And it's so great to get it in the context of the story you just told. Now I can picture it all much more vividly--what the Jim Crow south was really like.

I am still amazed by the wall. I had never heard anything like that before.

I wonder whether you've read the book, The Help, and if yes whether it rings true to your experience.

Jules and I both read it and enjoyed it, but wonder whether it was exaggerated to the point of cartoonishness at times. Your story makes us think maybe it wasn't.

Michael Healy

Jan 20, 2012 5:37pm

Haven't read it yet, nor seen the movie, but this discussion inspires me to do so.

Reality is stranger than fiction sometimes. Things really happened that you would think were exaggerations if you read it in a work of fiction. For example, I was on football, basketball, and baseball teams for Maxwell AFB which played against teams from around Montogomery (sponsored by Piggly-Wiggly, Montgomery Ward, etc). It wasn't unusual for us to be called n-----r-lovers by the opposing teams because the families on the airbase paid a significantly better wage (fair) to the "colored" maids who came to clean and help around the house. The locals resented that highly, as if setting a bad example and arousing false expectations.

Michael Healy

Jan 21, 2012 7:38pm

In The Gulag Archipelago, Alexander Solzhenitsyn describes how inhumanly the political prisoners in Soviet Russia were treated by the secret police and prison guards, whom he describes as "torturer executioners." However, after the criticism of others, he says (p.160):

So, by referring to the airbase as "a little island of the north set down in the middle of the deep south," that doesn't mean that the north was free of prejudice. It can take suble forms beyond mere legal prohibitions.

The riots of the '60's in Los Angeles, Detroit, and other cities outside the south showed that the problem was more widespread. I have noticed that the original deed to my house in Steubenville, Ohio built in 1956 has a clause in it (now struck through) forbidding sales to black people!

Further, while my sister and I were "educated" against prejudice, who knows how much we subtly absorbed from the culture. "Cleanse me of my unknown faults, O Lord."

Jules van Schaijik

Jan 21, 2012 9:30pm

Michael Healy, Jan. 21 at 7:38pm

I have noticed that the original deed to my house in Steubenville, Ohio built in 1956 has a clause in it (now struck through) forbidding sales to black people!

Wow.

lenore

Jan 23, 2012 5:28pm

As Michael's sister I would have something to add. I was 2 years older and do remember most of what he posted. I also have vivid memories of fearful situations. Just riding on a bus sitting in the front which was almost empty and seeing all the blacks crowded in the back of the bus and standing made me feel uncomfortable. During the bus strike, it was eerie riding through the streets of Montgomery seeing all the blacks walking. No one had cars, but no one would ride the bus. We had a "colored maid" at our home every day taking care of my 94 year old grandfather. She would walk to work every morning. I know it was a long walk. My Dad would drive her home evenings. However, she would sit in the backseat. No white man would dare drive through town with a colored woman in the front seat in that toxic atmosphere. As children it was confusing because kids sat in the back. In this case Mike and I would sit in front with Dad, and the maid would sit in back alone

lenore

Jan 23, 2012 5:55pm

During my dad's first tour of duty, we were part of an assigned group because most families were there for a short time and this encouraged military families to make friends and adjust. We socialized with this group: picnics, swimming, etc. At that time the military was desegregated. In our group was a black family. I often wonder now where the kids went to school. The public school next to the base and the Catholic school in town were both segregated. Mike is correct about the culture of the south being part of the Catholic school. The school was in an old southern mansion. The nuns lived in the house and classrooms were in the old slave quarters. When we moved north to Pittsburgh, I attended Sacred Heart school. My parents had to come to a parent teacher meeting because of the revisionist southern history that I was spouting. I had been taught that the Civil War was about states rights, not about slavery. The sister was completely appalled, and this precipitated a conference. I still do not trust politicians who use that language. I always suspect they are using code to justify something.

Jules van Schaijik

Jan 25, 2012 8:46pm

lenore, Jan. 23 at 5:55pm

I had been taught that the Civil War was about states rights, not about slavery. ... I still do not trust politicians who use that language. I always suspect they are using code to justify something.

I think there are many who hold that position today. I am not one of them, but from this video it seems that Ron Paul might be.