Kicking the Anasthesia Habit

Devra Torres | Jul 11, 2013

Something I constantly notice is that unembarrassed joy has become rarer. Joy today is increasingly saddled with moral and ideological burdens, so to speak. When someone rejoices, he is afraid of offending against solidarity with the many people who suffer. I don’t have any right to rejoice, people think, in a world where there is so much misery, so much injustice.

I can understand that. There is a moral attitude at work here. But … the loss of joy does not make the world better—and, conversely, refusing joy for the sake of suffering does not help those who suffer. The contrary is true. The world needs people who discover the good, who rejoice in it and thereby derive the impetus and courage to do good. Joy, then, does not break with solidarity. …[W]e have a new need for that primordial trust which ultimately only faith can give. That the world is basically good, that God is there and is good. That it is good to live and to be a human being. …

--Cardinal Ratzinger, Salt of the Earth

On the one hand, joy and merriment. On the other, the inescapable concerns and uncertainties (and occasional panic and terror) of someone in dead earnest about living and raising a family in interesting times.

How are we supposed to “multitask” that? The tendency is to pick one: either be crushed by darkness and apprehension, or else be cheerful, but with a meaningless cheerfulness—as St. Josemaria puts it:

the kind we might call physiological good spirits, like the happiness of a healthy animal.

(Not that there’s anything wrong with being at the top of one’s physiological game—it would be nice!—but it’s not supposed to be our loftiest goal.)

I think Pope Francis sheds light on the problem of happiness in this passage from Encountering Christ:

Do you have the courage to set out on the path that Mary chose, of caring for life from beginning to end? Or are you lethargic? And if you are… what is it that’s putting you to sleep? Mary did not allow anesthesia to interfere with love! And today we ask her: “Mother, may we love seriously, may we not fall asleep, and let us not take refuge in the thousand and one varieties of anesthesia that this decadent civilization offers."

What is it that’s putting us to sleep? There are plenty of possibilities, just as with literal painkillers. Some knock you out altogether, or at least make you groggy. Others deaden pain by rendering your whole inner world a little bland. (“It flattens everything,” a friend on antidepressants once told me.) Still others—the “recreational drugs”—draw you away from reality and its complications altogether.

With “spiritual anasthesia," there’s a similar variety. Just as some painkillers make you physically drowsy, certain actions--gluttony, sloth, technology overload--have the same effect.

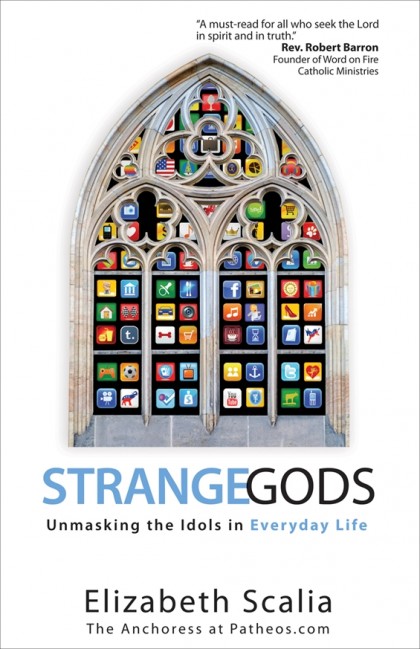

In other cases, we’re dulling our pain or diverting our attention by other means—maybe the “strange gods” Elizabeth Scalia speaks of in her very promising new book by that name

(and that's all I can say, not having read it yet). These could be sports or appearance, hobbies or politics, consumerism ...

What’s so important about being awake? Our eternal destiny turns on it, for one thing:

Let your loins be girded and your lamps burning, and be like men who are waiting for their master to come home from the marriage feast, so that they may open to him at once when he comes and knocks. Blessed are those servants whom the master finds awake when he comes.

Luke 12: 35-37.

Why is anesthesia, in all its many varieties, so popular today? Is this the brave new world—we’re all on soma? We've become so soft and lazy that we need to be told “Sitting is the new smoking,”

so lethargic that ordinary challenges seem too much to face without drugs or escapism?

My mother always reminded us not to pay attention to thoughts we had when we were very tired, and maybe we in the 21st century are in the grip of a collective exhaustion that makes it hard to see the good and face the bad. We’re prone to anxiety, depression, and suicide, and that strikes us as normal, not an emergency.

But we need to shake off the anesthesia and reject both physiological "happiness" ("a pig satisfied") and escapism. Benedict and Francis can show us the way, if we can stay awake long enough to listen.