More Things in Heaven and Earth

Devra Torres | Jan 28, 2014 | 1 cmt

We don’t know much.

This thought is a useful remedy for anyone inclined to nose around in other people’s consciences and make free about the state of their souls. Reflecting on just how miniscule our knowledge is, and how many, many unknown variables are at play is handy for warding off judgmentalism. It turns out gaze back on our own cluelessness and helps us realize how unqualified to pontificate we are.

But it can also have a more pleasant (and just as crucial) use. It reminds us to wonder.

If fallenness does anything, it makes us jaded. The “cares of this world” crowd out the pleasures of wonder. We get mired in the anxieties of wrestling the family budget into submission. Or trying to please all the voices inside and outside of our heads. Or worrying about how our childrearing or fitness level or piety measure up.

And even if we had all the leisure in the world, the malice and betrayals and inadequacy of other people still work against the cultivation of wonder. Being on the alert for betrayal or disappointment is a survival skill. As Jorge Bergoglio says in Encountering Christ,

What if we look at our world today and wonder what spiritual attitude has produced this civilization? Don’t we hear the word “disillusionment” echoing above all the rest?

Whatever may be going on beneath the surface of our perception, our instincts tell us, it’s probably not good. It’s probably not even neutral. Maybe it’s unsafe, like the poisonous GMO’s lurking within that wholesome-looking ear of corn,

that inviting loaf of fresh-baked bread.

Maybe it's tragic, like the ugly secrets .lurking within your friend’s seemingly happy marriage. Maybe it's poisonous, like childrearing methods with the wrong mixture of authority and indulgence.

Maybe it's tragic, like the ugly secrets .lurking within your friend’s seemingly happy marriage. Maybe it's poisonous, like childrearing methods with the wrong mixture of authority and indulgence.

Which is why it’s good to pay attention to things like this:

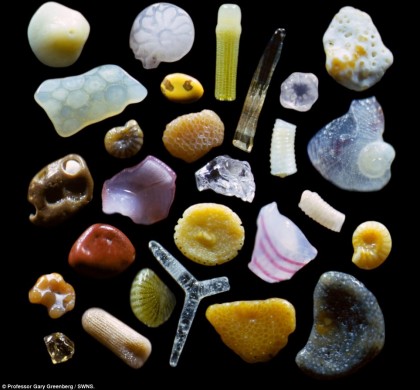

This is a photo of a few ordinary grains of sand, but magnified.

So is this:

And here’s how it looks even closer:

It was there all the time; we just lacked the technology to perceive it.

It was there all the time; we just lacked the technology to perceive it.

Then there’s the song of crickets, slowed down, sounding like what people have called “a choir of angels,” “the music of the spheres,” or simply “God’s cricket chorus.”

Listen for a minute (via the link above); you’ll see what I mean.

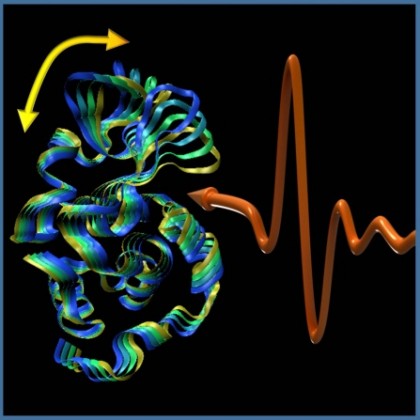

Also, it turns out that the proteins of cells in the human body vibrate, at carefully calibrated frequencies, like the sustained notes of a ringing bell as they go about absorbing oxygen, repairing cells and replicating DNA. One writer calls it “the symphony of life.”

If God is doing all these dazzling and mysterious things just below the surface, on the material level, in ways that our instruments are just beginning to pick up, what makes us think that in the spiritual, or the interpersonal, world, it’s not the same?

If our instincts tell us everything hidden is likely to be dark and dreadful, or else prosaic and in need of de-mythologizing, maybe we should question our instincts We’re like middle schoolers on a mandatory field trip to the Louvre, arrogant in our obliviousness.

We’re surrounded by masterpieces that we’re too gauche to discern. We’re preoccupied with trivia, wondering when we’ll be allowed to buy trinkets at the gift shop, disgusted that the snack bar doesn't carry our favoirte flavor of Pringles.

Socratic ignorance may not be bliss.

But it's a big improvement on the swaggering, jaded kind.

Comments (1)

Kate Whittaker Cousino

Jan 29, 2014 11:06pm

Oh, yes, Devra! And if creation has such wonders hidden in it, how much more do the people around us, created in God's image? All those layers of mystery, with occasional glimpses into the subjectivity beneath, those hints of eternity? And yet we label, dismiss, and assume the worst of each other.