On Culture Shock and Spiritual Fibromyalgia

Devra Torres | Jun 30, 2013 | 8 cmts

I want to continue our conversation about the “self-referential person”--the one who lights a lamp but then gets scared and hides it under a bushel, reluctant to go out into all the (contaminated) earth to preach the gospel.

We can agree there's a big differentce between fearful, self-imposed isolation and the legitimate effort to found new communities and develop a sense of identity for oursleves and our descendents.

That doesn't let us off the hook completely, though: we still have to discern--over and over--when and how to engage the culture and when and how to repudiate it. St.Augustine's speaks of the Israelites taking "gold out of Egypt"

--a metaphor for embracing whatever good is to be found in a culture. We have to do the same, keeping an eye out for the "fool's gold" mixed in with it. (A relative's insistence that Twilight was a nice, wholesome story about chastity comes to mind.) When to embrace, when to adapt, when to reluctantly reject, when to run screaming in the other direction--no blueprint in the form of established childrearing norms is about to materialize to assist us. As Katie points out:

When there's natural community, we have a way of life handed down to us. When that breaks down everything has to be questioned, examined, figured-out, re-assembled, doubted, [and] second-guessed, etc., which is exhausting

and:

I'm pretty sure there's a link between the breakdown of natural community life and the kind of discernment-fatigue people like me suffer, which seems to me a sort of spiritual fibromyalgia.

Katie continues:

Still, I agree with you very much about the insubstitutability of personal judgment. And maddening as it sometimes is, it does seem to me a kind of calling for our generation.

Jules contributed striking a quote from Glenn Tinder:

The condition of mass disintegration… intensifies human guilt… by depriving people of traditional and accepted patterns of life… Often parents are left only with a few notions vaguely based upon the hypotheses of unknown, and frequently philosophically ignorant, psychologists. This of course constitutes an opportunity for a very creative kind of parenthood. But to have to train children and, in addition, to determine the final ends and the methods of such training is about as difficult a responsibility as a human being could assume. Parents who accept this responsibility are required, implicitly, to choose among competing philosophies of man, the world, and civilization; furthermore, they have to do this when they are young and inexperienced and must, on the validity of their choices, stake in some measure the lives and happiness of their children. Never can it have been more true than today that the sins of the fathers are visited on the children.

I wholeheartedly agree. But here's the silver lining:

The comforts of a "traditional and accepted pattern of life" can be a decidedly mixed blessing. I once spent an entire decade in a sustained state of culture shock—precisely because I felt trapped in a “natural community,” bound by some very definite “traditional and accepted patterns of life.”

Our family had moved to Barcelona, where my husband was teaching, earning his doctorate, and generally holding things together for all of us. There were various reasons for my abject failure to adapt, but one stumbling block was the omnipresence of the unwritten rules: a “that’s just the way it’s done” for every occasion—in everybody’s mind but mine.

It felt totalitarian. The rules invaded every nook and cranny of life, from the proper kind of ham for your tostada at merienda to the single correct way to part your hair to the bearing and rearing of your children.

Some of these rules were clearly better than what I was used to, for instance:

- Don’t go around looking like a slob (even if you’re very, very old, young, tired, or pregnant).

- Don’t eat lunch alone at your desk.

- Don’t get fat.

In some cases they were worse:

- Don’t insist on a carseat for your baby.

- Send your toddler to all-day preschool.

- Don’t be caught dead wearing last season’s fashions.

And sometimes they were just different:

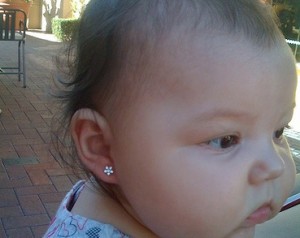

- Pierce your little girl's ears.

- Eat supper at ten o'clock at night.

In America, of course, we have unwritten rules, too—but many of them are along the lines of

- Do your own thing.

- Hey, whatever works for you.

Now, even I could see that living in a natural community—foreign or not—had one distinct advantage: If you’re not continually occupied with designing, evaluating, and second-guessing all the creative decisions you’re forced to make, your mental energy can occasionally be turned towards other things! Someone has already invented the wheel: you’re free to drive the car. Whole swaths of daily life can (to switch metaphors) be put on automatic pilot.

Of course, the personalist ideal is not passivity and unreflectiveness. Automatic pilot alone will never lead you to "become who you are." Our most personal actions are not the ones we perform in reflexive mimicry of a collective expectation. That doesn't mean we have to reflexively reject expectations, either.

But if some things are on automatic pilot, it allows us to concentrate on the truly "human acts" in which our freedom, rationality, and self-possession are fully engaged.

So here's the silver lining: we have the unique opportunity to enjoy the best of both worlds. In 2013 American, most of us don’t have that option of reflexively conforming to a prefabricated set of cultural norms. We therefore don't have the temptation to delegate discernment to our ancestors entirely.

But we need not ghetto-ize. It's possible to join, or found, a micro-community of the kind John Janaro (and then-Cardinal Ratzinger) have referred to, one which enriches the world rather than just running from it, inviting people in, offering them an alternative to the toxic, disintegrating ruins around them. We want ot make sure to avoid the kind of cultish tendencies Katie discusses here, but these are not inevitable.

I think it's true: this is our generation's calling. We're living on a construction site,

not in the suburbs.

It promises to be exhausting. But it doesn't have to be embittering, and it's not likely to be boring. Besides, every calling comes complete with the grace to carry it out.

Comments (8)

Tim Cronin

Jul 8, 2013 1:19pm

We are seeing the collapse of the Enlightenment experiment with a hyperpluralist society and totalitarian government of technology and secularism. An unsubstantiated "right" of life, liberty, and happiness against all others has led to the "right" to kill the unborn, the "right" to mutually agreed to immoral acts, and the avarice of having all the latest technological toys. (cf Brad Gregory: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society). It is a time for something new with the monotheistic religions playing a major public role. -Tim

Devra Torres

Jul 10, 2013 10:11pm

Tim, yes, "hyperpluralist" is a good way of putting it. I don't think the problem lies in positing rights, though, but in divorcing them from responsibilities and from the truth about the person.

Tim Cronin

Jul 12, 2013 7:21am

Yet this is precisely what the Declaration of Independence and Constitution did. It privatized religion and institutionalized a Lockean conception of rights as rights from others. I don't think there is any avoiding a collapse without a reformation of our government structures and moving it away from Enlightenment and secular principles. We need a form of government that has a public role for religion with its conception of the person to avoid a hyperpluralist collapse. (What is divided can not stand)

Devra Torres

Jul 15, 2013 8:54pm

Tim, this is a big question, probably bigger than I should try to address in a comment or two. But here's a starting point: what do you mean by "rights from others," and is there a different conception of rights that you think would be useful as a foundation?

I've been wanting to write about a talk I heard on Mary Ann Glendon's First Things article, "The Bearable Lightness of Dignity," where she talks about how "human rights" talk makes sense as long as it's based on the idea of human dignity, which is, like it or not, a Christian idea. The whole thing falls apart once the common ground it was originally erected upon disintegrates.

Tim Cronin

Jul 15, 2013 9:28pm

David Schindler probably explains it best in this article: http://www.communio-icr.com/files/Schindler_Repressive_Logic_of_Liberal_Rights.pdf

this liberal idea, and the

juridical order of rights based thereon, are governed by a hidden metaphysics of formal-indifferent freedom, and that the hidden nature of this metaphysics is just the point. In other words, it is endemic to liberalism’s formal freedom and juridical rights that no definite metaphysics be announced on their behalf regarding the nature of the

human person vis-à-vis relations to God and others, and to the true and the good. My argument, in this light, is that the proposal of such freedom and rights thus involves of its inner logic a hidden “dictation” of just such a metaphysics. Precisely in the name of a formal nature that would be absent of such relations, the proposal makes

present a fragmented and so far reductive form of the relations. The proposal of liberalism thus, in a word, involves what Ratzinger/ Benedict XVI has termed a “dictatorship of relativism.”13 In the name of the avoidance of any definite metaphysics of the person in relation to God and truth (hence relativism), liberalism eo ipso “imposes” a formalistic metaphysics of the person (hence dictatorship).

Tim Cronin

Jul 15, 2013 9:29pm

cont'd:

The point, in other words, is that, on the liberal

reading, rights are rooted precisely in a formal-independent, and so far

adult-like, “strong” freedom that has been originally abstracted from

any natural order of relations to, and so far from any natural order

of dependence upon, God and others, and to transcendent truth and

goodness. The claim to rights by the “strong” in this sense always,

as a matter of principle, trumps in advance the claim by those—the

“weak”—whose rights are tied to this natural order of relations,

when and insofar as these respective claims enter into competition

with each other. The claim to rights by the “strong” thereby also

trumps the claim of those who would protect the rights of the

“weak” in the event of such competition

Tim Cronin

Jul 15, 2013 9:34pm

I think we would need to enshrine a definition of the person as related to God and others and finding his purpose in these relations to have an adequate basis for resolving conflicts. The idea of "rights" seems to automatically speak of individualism and competition. I'm not sure what's the best way forward but I've started to read John Milbank's political theology and I think he probably has some good ideas for how to move forward.

Devra Torres

Jul 22, 2013 2:50pm

Tim, my apologies for the delay--it's been a week of family chaos, during which I've also been pondering and discussing these questions. I hope I can address them in a post soon.

When you say (back in your second comment) that we need "a form of government that has a public role for religion," do you mean we should have an established religion? It seems to me that America's founding documents certainly didn't provide for abolishing a public role for religion, despite relatively recent attempts by judges and others to pretend they did.

It also seems that "rights" need not be understood as individualistic and competitive, but can be understood as deriving precisely from the nature of the person. The Founding Fathers differed in their theology and their ideas of the truth about the person, but the "rights" they've bequeathed to us go beyond the "right to be let alone" and have also been understood as something that derives from the God-given nature of the person, regardless of social status or blood.

Well, with that, I don't pretend to have addressed all your points, but I wanted to revive the conversation. More as time allows.