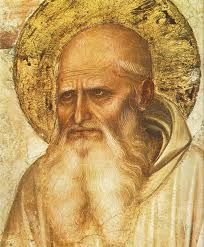

St. Benedict and phenomenology

Katie van Schaijik | Jul 11, 2012 | 29 cmts

The key to the kind of phenomenology Jules and I studied, which is sometimes called "realist phenomenology" or "von Hildebrandian phenomenology" is a reverent, attentive listening to the voice of Reality, to "things in themselves." It sees "the art of living" as a matter of "receiving" what we find in reality, and responding to it faithfully. It stands in contrast to a way of philosophizing that is more concerned with constructing conceptual systems, or with studying texts.

One of the key features and contributions of von Hildeband's thought, in particular, is a rehabilitation of the role of the heart, not only in human relations, but in our apprehension of Reality. The heart is not just "the seat of the passions", belonging to our animal nature and needing to be ruled by our "rational part". Rather, it is, in a way, the locus of the person, the center of our being.

From this point of view, the very first lines of the Rule of St. Benedict have always struck me as having a deep spiritual affinity with our school of phenomenology. And it is not surprising or coincidental that Dietrich von Hildebrand and many of his friends and disciples became Benedictine oblates.

Here it is:

Listen, O my son, to the precepts of thy master, and incline the ear of thy heart, and cheerfully receive and faithfully execute the admonitions of thy loving Father, that by the toil of obedience thou mayest return to Him from whom by the sloth of disobedience thou hast gone away.

I think it's right to consider him among the patron saints of the Personalist Project, and today among our special feasts. St. Benedict, pray for us.

Comments (29)

Katie van Schaijik

Jul 11, 2012 11:39pm

Some years ago, when we were living in The Netherlands, and I was undergoing some inward trials, I found grace through the ministrations of a Jesuit priest, who lived and worked at a Benedictine convent of perpetual adoration. I retreated there often. And so great was the help I received, that I thought to myself: "If ever God gives us another son, I would like to name him Benedict."

He did, and we did. In 2003, our fifth child, Benedict Francis, was born.

Two years after that, we had a new Pope—a new personalist Pope!—who chose the same name.

Kevin Schemenauer

Jul 12, 2012 10:28am

I have heard or read somewhere that Dietrich von Hildebrand was a third order secular Franciscan. Is this true?

Katie van Schaijik

Jul 13, 2012 1:56pm

Kevin, DvH was a great devotee of St. Francis. He grew up in a beautiful villa--formerly a convent—in Florence called San Francesco. The great catalyst to his conversion was a passionate discourse by Max Scheler on the nature of holiness, using St. Francis as the central example. He named his only child, a boy, Francesco. But, if I'm not mistaken, he was never a third order Franciscan. The spiritual discipline he chose for himself was Benedictine. He was a Benedictine oblate for decades, faithfully praying the Liturgy of the Hours.

I asked his widow once about his spirituality. She said the key to his spiritual life is the liturgy. I imagine that's what drew him to Benedictine spirituality—its liturgical focus.

But I will ask her later, just to be sure. (She lives with us in summer.)

Katie van Schaijik

Jul 13, 2012 2:03pm

Meesebellbee, thank you for such kind encouragement! I can't tell you how much the feedback keeps us going.

Edith Stein got to Göttingen just after DvH, so they missed each other. But both were profoundly influenced by the same three great teachers: Edmund Husserl, Adolf Reinach, and Max Scheler. (Scheler was not formally a teacher, but he was a gigantic personal and intellectual presence, enlivening pub discussions with his overflowing genius.)

I believe they did meet once or twice later, but didn't know each other well.

I'll ask Lily about this too. I know she's been working on article comparing her husband and Edith Stein.

I don't know about Edith Stein's relation to St. Benedict.

Patrick Dunn

Jul 15, 2012 7:01am

I'm partial to St. Ignatius of Loyola as a personalist saint, with his emphasis on the role of the affective dimension of the person in discernment. I think one also finds that same "attentive listening to the voice of Reality" in Ignatius - most of all, the listening to the Holy Spirit in an attempt to find God's will for the person in all things.

Katie van Schaijik

Jul 15, 2012 1:57pm

I must say the best spiritual direction—maybe the only really good spiritual direction—I ever got came through a Dutch Jesuit priest, of all unlikely creatures. It was highly personalistic. Rather than giving me advice according to his own ideas and experience, his whole effort was to help me learn to listen to the voice of the Holy Spirit speaking in my own interior and circumstances. But apart from that, I've never been able to get a feel for St. Ignatius. And I have had some bad encounters with Jesuits.

One of the most enjoyable philosophy lectures I ever heard was by a Franciscan friar, Allan Wolter, a scholar of Duns Scotus. He, too, was very personalistic. At the end of his lecture, he recited the poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins (a Jesuit!) that he thought beautifully captured Scotus' stress on individuality.

As Kingfishers Catch Fire

It's one of my favorite poems. Rumer Godden's novel with the same title is one of my favorite books.

Jules van Schaijik

Jul 15, 2012 7:27pm

Good point Patrick.

It would be interesting to think through these two aspects of Jesuit spirituality, the one you mention, which seems deeply personalist, and the other, much more disciplinarian in nature (and sketched, for instance, in some memorable passages from John Henry Newman) which seems much less so. I wonder how these two aspects hold together. Do you have any insights on that?

Tim Cronin

Jul 16, 2012 9:51am

In Esther De Waal's book "Seeking God: The Way of St Benedict" she writes about how the word hearing and the word obedience come from the same root etymologically. Obedience means "to hear". I also like how she seemed to refer that hearing to those around us. If today you hear his voice harden not your hearts. Often I don't hear his voice because I harden my heart to those around me. I also think St Benedict has a lot to teach us about stability in an age of mobility.

Patrick Dunn

Jul 16, 2012 6:30pm

Jules van Schaijik, Jul. 15 at 6:27pm

Good point Patrick.

It would be interesting to think through these two aspects of Jesuit spirituality, the one you mention, which seems deeply personalist, and the other, much more disciplinarian in nature...

Do you have any insights on that?

Jules, do you have something specific in mind regarding the more disciplinarian aspect of Ignatian spirituality? I'm just trying to understand what you're referring to, and perhaps then I can respond.

Jules van Schaijik

Jul 17, 2012 9:18am

I don't know much about St. Ignatius or the spirituality of the Jesuits. The few encounters, however, I have had with Jesuits incline me to think that Newman's sketch of them, though exagerated to make a point, contains a lot of truth.

The passages below are lifted from a talk Newman gave to the oratorians in Birmingham. (His aim, as he says, is to shed light on the Oratorian way of life, not to do full justice to the Jesuit.)

Jules van Schaijik

Jul 17, 2012 9:20am

Jules van Schaijik

Jul 17, 2012 9:20am

Jules van Schaijik

Jul 17, 2012 9:21am

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 10:54am

Jules,

When I first wrote my comment, I had in mind my own experience (as a non-Jesuit) of Igantius through the spectrum of "Ignatian Spirituality," which I take to have a broader meaning than how it would apply to religious life as a Jesuit. There is a difference, I think: one can be, in many ways, Ignatian, without being a Jesuit, just like one can be, in many ways, Benedictine or Franciscan, without being a religious of those traditions.

And so originally, I was only thinking of what may be the more disciplinarian aspects of the spirituality that could affect anyone who is otherwise drawing from it, and I had in mind, if anything, Ignatius' teaching on penance, moderation, thinking with the Church, maybe more besides. But my larger point was going to be that, granting the fact that in my own experience the disciplinarian aspect was not at the forefront, such an aspect would stand to serve the greater and more profound goals of freedom from disordered desires and affections, realization of our true selves before God, holy indifference, authentic discernment of one's identity and mission/vocation, and more besides - which I take to be fundamentally compatible with personalism as I understand it.

...

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 11:02am

But I see from the Newman quote that your question has more strictly to do with Jesuit life than I anticipated. And I could only speak in a very limited way to that, if at all:

I'd say, first, that my own exprience of Jesuits is that they are not predominately disciplinarians, if you will. I've actually experienced them to be quite the opposite in most cases. Still, I recognize that the governing structure of the Society plays a role in their lives at least, and I've known Jesuits to speak about their assignments (in most cases) such that they've been asked for their personal input on where they'd like to be stationed, for instance, though ultimately the decision belongs to a particular Superior.

Which brings up the second point: I just recently was reading from Encounters With Silence by Karl Rahner, SJ, and in one chapter ("God of Law"), he seems to raise the same difficulty you did. I don't think I could say any more than he did and so will simply quote some of what I read:

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 11:04am

"The only answer seems to be that, whenever I obey such a law, I must keep looking directly at You, In this way I can pay homage to You, directly and exclusively, and not to the thing that is required of me, not even to the thing as the reflected splendor of Your Being. Precisely because there is in the thing itself nothing to which I can give my heart without reserve, obedience can be the expression of my seeking You alone in it.

...

If I look upon the obedience to these laws as a demonstration of homage for Your beloved free Will, which rules over me according to its own good pleasure, then I can truly find you therein. Then my whole being flows toward You, into You, into the broad, free expanse of Your unbounded Being, instead of being cramped within the narrow confines of human orders. You are the God of human laws for me, only when You are the God of my love."

It seems he finds here a concrete way to personalize not only the otherwise 'dead' letter of the laws that he is to obey, but also his own intense love for God.

Jules van Schaijik

Jul 18, 2012 12:40pm

As I said, I am out of my depth here. The main contrast that Newman and von Hildebrand have in mind is between two ways of shaping character and striving for holiness. One focusses on acts of obedience, acts of the will, and self-control, the other more on encouraging and guiding the interior movements of the heart. The former inevitably gives more attention to general rules, the latter more to the unique self. The second approach is more personalist in spirit, but the first is certainly not against or incompatible with personalism. On the contrary, obedience and self-control are absolutely necessary.

And, of course, our ability to force ourselves to do something we would much rather not, something that goes very much against the grain, is central to the dignity and responsibility of being a person.

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 12:52pm

Thank you, Jules. It's interesting to me to reflect on my own perceptions of ways of striving for holiness, especially in comparison to some of the points raised within this post.

For instance, my perception of Benedictine spirituality has been that it's focused on "acts of obedience, acts of the will, and self-control," and so to me has seemed to be rather disciplinarian and non-personalistic. I haven't felt very inclined to it myself. And I was surprised initially to find that Katie saw St. Benedict as a patron of personalism! Yet, I know from reading some Benedictine writers that they do indeed give focus to "guiding the interior movements of the heart."

In a similiar manner, my own perception of the Ignatian approach has been that's predominately focused on "guiding the interior movements of the heart" - this is how I understand, more or less, Ignatius' "discernment of spirits" which is at the heart of his Exercises. Yet, it seems others do not perceive the Ignatian approach this way.

...

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 1:03pm

Further, the Ignatian approach seems to me to give more attention to the unique self (instead of general rules) than the Benedictine approach. Ignatian thought is very personal, concerned not simply with the generalities of conversion, but with how I should go about such conversion, and what God is calling me to here and now. There is an immediacy to it, I suppose, that I do not find with the Benedictine approach. The latter seems to me to be more abstract and somewhat distant, a blueprint perhaps that all are meant to operate within, but not something that has the same intimate relevance.

Even the "rules for the discernment of spirits" from Ignatius are meant to guide an individual as to how God is uniquely present to him or her here and now, and then how to respond in kind. The "rules" are not even really rules, but principles that we sift our own experiences through - they 'reveal' to us the meaning of the raw data that are our very lives. The Spirit is the author the conversion, ultimately, and God's immediate encounter with the soul excites me. The Ignatian dynamic of an active passivity too seems to protect one from perfectionism or conformism to a predefined mold of holiness.

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 1:15pm

Describing Ignatius' own favorite manner of prayer (the daily examen of consciousness) besides the Mass, and one which still is central to Ignatian spirituality today, one Jesuit writes:

"The examen we are talking about here is not a Ben Franklin-like striving for self-perfection. We are talking about an experience in faith of growing sensitivity to the unique, intimately special ways that God’s Spirit has of approaching and calling us. Obviously it takes time for this growth. But in this sense examen is a daily renewal and growth in our spiritual identity as unique flesh-spirit persons loved and called by God in the inner intimacy of our affective world. It is not possible for us to make an examen without confronting our own unique identity in imitation of Christ before God."

How beautiful this is to me!

Jules van Schaijik

Jul 18, 2012 2:37pm

I'm learning a lot from all you say, Patrick, and promise not to make any more claims about Benedictine or Ignatian spirituality until I know them better first-hand. I will limit myself to the ideas themselves, without attributing them to one spirituality or the other.

The "immediacy" you refer to makes the abstract concrete, and the theory practical. It goes from, say, "love your neighbor as yourself" to "give John, who always forgets his lunch, half the sandwich you are about to eat." But don't you agree that this kind of immediacy can still bypass the unique center and interiority of a person? I think it can be so immediate that it eliminates the space and time required for that person to collect his own thoughts, recall his priorities, and make his own decision. From this point of view, general principles may be better suited to activating a person's free, spiritual center.

Incidentally, John Crosby touches on this issue in our last reading circle text (pp. 158-160). A physician, he thinks, should refrain from saying somethings like "if I were you, I would choose this treatment," so that the patient is "forced" to make his own decision.

Jules van Schaijik

Jul 18, 2012 3:00pm

This comment by Rhett Segall, which draws a contrast between a premature, willed forgiveness, and a heartfelt forgiveness nurtured by grace, is apropos here also.

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 3:48pm

I didn't mean to chastize you, Jules! All that I wrote of Benedictine spirituality was my own limited perception of it, how it has seemed to me, how the particular dynamics of it have resonated with me (or not). (I think I understand Ignatian spirituality more than Benedictine, in general, as I've studied it more intensely, with greater interest, and simply have found it particularly effective for me.) But in theory, I think both spiritualities are meant to arrive at the same end and can accomplish in the one who employs them the same fundamental fruits. I do not want to be critical in such a way as to suggest a real flaw in the Benedictine approach.

By "immediacy," I did not necessarily mean to highlight the temporal aspect (as in, deciding quickly or overridng the 'space' required to actually make a free choice), though my sense is that as one grows in the art of discernment and intimacy with God, one is typically more capable of finding one's own authentic response more readily than when one was not so far along on the journey.

Certainly, much wisdom is gained in hindsight (life lived forward, understood backwards) and the prayer of examen incorporates this facet of learning.

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 3:49pm

One of the potential ‘limitations’ (though I think of it more as a necessary part of growth) of the Ignatian immediacy is that it can entail something of a trial-and-error dynamic. The writer I linked to prior writes of future-oriented fruits from our backwards-oriented prayer that “there should be a great desire to face the future with renewed vision and sensitivity as we pray both to recognize even more the subtle ways in which God will greet us and to recognize the Spirit calling us in the existential situation of the future, and then to respond to that call with more faith, humility, and courage.”

The immediacy I had in mind indeed makes the abstract concrete, though it is more than a movement from a general principle to a concrete, particular application. What is immediate most of all is that encounter with the Spirit, who we are meant to respond to from our unique center and interiority—it is a communion always of two persons: my own personhood and that of God.

...

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 3:49pm

This approach, I believe, transcends a moralistic approach of what ought to be done in a given instance. It asks us to learn with the heart. It is fundamentally discipleship, an active listening to Reality that is meant to become second-nature, habitual (but not stale or formalistic), such that communion with God is always occurring (that is the hope, the yearning, at least).

The whole praying of the examen in this way tends towards noticing at the decisive time (to recall your sense of “immediacy”) how our own unique center and interiority is meant to engage God ‘on the spot’ – to become contemplatives in action is the goal. Because this is more like acquiring a taste or knack for something than it is attempting to deduce something, there is a learning curve, and so realizing that temporal “immediacy” of the “immediacy” of God and the call of the moment develops, probably in proportion to our growth in self-knowledge and prayerfulness otherwise.

The writer of the article, speaking of St. Ignatius describes all of this well, I think:

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 3:52pm

“’Whenever he wished, at whatever hour, he could find God.’” (Autobiography, #99) This is the mature Ignatius who had so fully allowed God to possess every ounce of his being through a clear, abandoning Yes that radiated from the very core of his being, that he could be conscious at any moment he wanted of the deep peace, joy, and contentment (consolation, see the Exercises, #316), which was the experience of God at the center of his heart. Ignatius’s identity, at this point in his life, was quite fully and clearly “in Christ”: “For now my place is in him, and I am not dependent upon any of the self-achieved righteousness of the Law.” (Philippians 3:9)

Being able to find God whenever he wanted, Ignatius was now able to find that God of love in all things through a test for congruence of any interior impulse, mood or feeling with his true self. Whenever he found interior consonance within himself (which registers as peace, joy, contentment again) from the immediate interior movement and felt himself being his true congruent self, then he knew he had heard God’s word to him at that instant.

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 3:53pm

And he responded with that fullness of humble courage so typical of Ignatius. If he discovered interior dissonance, agitation, and disturbance “at the bottom of the heart” (to be carefully distinguished from repugnance “at the top of the head” [John Carroll Futrell: S.J., Ignatian Discernment (St. Louis: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1970), p. 64.]) and could not find his true congruent self in Christ, then he recognized the interior impulse as an “evil spirit” and he experienced God by “going against” the desolate impulse. (cf. Exercises, #319) In this way he was able to find God in all things by carefully discerning all his interior experiences (“spirits”). Thus discernment of spirits became a daily very practical living of the art of loving God with his whole heart, whole body, and whole strength. Every moment of life was loving (finding) God in the existential situation in a deep quiet, peace, and joy.

...

Patrick Dunn

Jul 18, 2012 3:54pm

For Ignatius, this finding God in the present interior movement, feeling, or option was almost instantaneous in his mature years because the central “feel” or “bent” of his being had so been grasped by God. For the beginner, what was almost instantaneous for the mature Ignatius may require the effort of a prayerful process of a few hours or days depending on the importance of the movement-impulse to be discerned. In some of his writings, Ignatius uses examen to refer to this almost instantaneous test for congruence with his true self—something he could do a number of times every hour of the day. But he also speaks of examen in the formal restricted sense of two quarter-hour exercises of prayer a day.”

(I apologize for the many posts, long quote - I just thought it was worthwhile.)

Ideally, the “formal restricted sense” fosters in us that “instantaneous” sense over time.

I’m glad to have that contribution from John Crosby, too. Just yesterday I did the “If I were you …” thing to someone, and I didn’t give it a second thought.

Jules van Schaijik

Jul 18, 2012 4:35pm

Patrick Dunn, Jul. 18 at 2:48pm

I didn't mean to chastize you, Jules!

Oh no, I never thought you did. But your understanding of Ignatius and his Exercises make clear to myself that my own is pretty superficial and based on only a few impressions. Better, therefore, to illustrate my thoughts on personalism, the heart, the will, etc., with things with which I am more familiar.

I find your comments only helpful. (And, if ever you think I need chastizing, I hope you will not shrink from the task.)