Assessment Run Amok

Devra Torres | Dec 7, 2014 | 2 cmts

When we started homeschooling, I was apprehensive about a good number of problems that turned out to be imaginary.

One was whether I’d enjoy my children's company if I were with them all day, every day. (I did: it turned out they were much more pleasant people when they weren’t in a state of chronic exhaustion.) Another was how on earth I’d find time for all the testing and quizzing I’d need to do to assess their learning.

A week in, I abruptly stopped worrying about that one. To tell the truth, I now knew more than I wanted to about their strengths and weaknesses: more, even, than I’d learned in nine years as a parent who went to all the meetings and helped with all the homework.

Karen Hendren and Nikki Jones, two first-grade teachers, recently made headlines as conscientious objectors to the Testing Run Amok model of education. They wrote a letter to explain to their students' parents why they were risking their jobs by opting out unilaterally.

Their letter was published by the Washington Post and can be read here. (Read the whole thing to get a sense of what affectionate and dedicated teachers these two are.)

As Hendren and Jones explain:

In our classrooms the children spend, on average, 1,510 minutes (25 hours) completing assessments. …. When you break down our days and count for specials, lunch, and recess, we end up with about 4 hours of instruction time. So, 288 instructional hours, or 72 days… yes, 72 days of our school year we, as teachers, are tied up assessing students …

Of course, you have to determine some method of evaluating whether learning is occurring or not. While it's true that you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink

you still have to assess whether he’s taken in the water or not.

Hendren and Jones are not against testing per se either:

We understand the need for assessments. ... We value data. However, we went to college for an understanding on how to do this. We both build in-depth, all-encompassing portfolios that are a TRUE picture of the growth of our students. These portfolios do not just show math and literacy, they also show growth in cognitive development, writing, understandings of every state standard, art, identity of self, science, social studies, social-emotional development, and more … Believe us, we know where our students are.

The more you’re invested in knowing your particular students, the less dependent you are on generic measures of success. I've found assessment so surprisingly easy because mothers are naturally invested in their own kids. But there are plenty of classroom teachers who know their students intimately because they're so dedicated to them. For them, the endless assessments are an obstacle, not a help.

Of course not all testing is useless or harmful. Reducing the sheer quantity of tests could help, and so could attention to the kind of test used. One of the assessments described "is designed to reach a failing point for each child." The teachers tell of what intense distress it provokes in every kind of child--the gifted, the insecure, the special-needs, the English-as-a-second-language. The system makes no distinctions and leaves nothing to the teachers' discretion. It doesn't just make the kids feel bad; it yields spectacularly inaccurate results.

So maybe using different types of tests, and fewer of them, would solve part of the problem.

But when Hendren and Jones took their concerns to the higher-ups, they suggested that they spend more time doing practice tests, mini-tests, and teaching to the tests. This, the administrators imagined, would diminish the six-year-olds’ stress levels. They seemed to think that somehow nothing else would be displaced by earmarking even more time not only for assessment, but also for pre-testing to alleviate the stress of assessment.

The art of teaching, which Hendren and Jones had spent years mastering, was treated as superfluous, as was the content of the instruction and the learning itself.

Hendren and Jones conclude with an inarticulate but moving expression of their belief that neither they nor the children are robots or machines or interchangeable parts.

So, families, here we are. We want you to know that we whole-heartedly love your children. We value and respect them. Your children are more than a number to us. They deserve more time in a rich learning environment, interacting with others, and growing deeper across academic and developmental domains. They do not deserve to be plugged into computers like robots. ...

Education is about finding the deeper meaning. Education is about acting upon curiosity and utilizing creative attributes to figure something out. Education is about highlighting multiple intelligences and valuing uniqueness. Education is not squelching. Education is not standardization.

I see what they mean. Of course, you can go overboard in the other direction.

To hear some experts tell it, nobody should dare to present a multiplication fact before ascertaining each student's temperament,learning style, and dominant intelligence. That was another of my imaginary problems when I began home education. What if I got mixed up and tried to teach the phlegmatic with the spatial intelligence and kinesthetic learning style in a way more appropriate to the extrovert with the emotional intelligence and auditory learning style? What if I ran out of time to customize each lesson eight different ways?

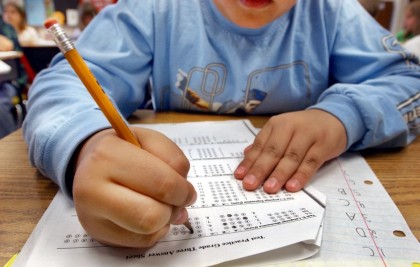

In fact, we have been known to pracitce multiplication tables and Latin declensions to the rhythm of a mini-trampoline. We've also been known to hole up in the basement for hours on end, filling in little ovals with a number two pencil. I use my knowledge of my students to try to find the balance, and I have discretion to do what makes sense for us.

But there's no reason classroom teachers shouldn't be allowed to use their common sense and do the same.

Comments (2)

deb

Dec 12, 2014 10:13am

My husband and I read this together and it was excellent! We often run into objections regarding homeschooling and the false impression that homeschoollers are incapable to assess their own students or even teach them properly, confronting questions like "How can you know they learn what they are supposed to learn?" Now, we can say our daughter graduated from a university cum laude while our other children are on the dean's list. Shut my mouth!! (Or rather "their"mouths!!)

Al and Deb

Devra Torres

Dec 15, 2014 12:37pm

Yes, it's so nice to have "objective" evidence for the skeptical. I have nothing but respect for teachers who manage to give personal attention to many students. We do our homeschooling with a large amount of delegation and keeping a close eye on our own objectivity, but assessing where the kids are has certainly not been a problem!