A God of Low Standards? The Ins and Outs of Mixed Motivations

Devra Torres | Mar 8, 2018 | 4 cmts

One of the most illuminating aspects of Catholic theology is the distinction between perfect and imperfect contrition. If you're going to go to confession, you need to be sorry for your sins. If you have no sorrow for sin at all, then confession's an exercise in hypocrisy--you're just feigning sorrow.

Or maybe you're indulging in magical thinking--you're neither sorry nor pretending to be, but you believe that by walking into a certain booth and saying certain words, regardless of what's going on in your heart, you can "produce" absolution.

So if you want to avoid hypocrisy or superstition, you need contrition.

But what kind of contrition? How much, exactly? How high a holiness bar do you have to aim for?

Here's where the distinction between perfect and imperfect contrition comes in. If you're sorry purely because it pains you to have offended God, who is so good and loves you so much--and therefore you have no attachment at all to even the smallest of venial sins--that's perfect contrition.

If, on the other hand, you're genuinely sorry (not just sorry you got caught), but mixed in with your more noble contrition is some self-centered concern, or even terror of "the loss of Heaven and the pains of Hell"--as one traditional Act of Contrition has it--then God will not withhold His forgiveness. He would like to see you reach greater purity of intention, but He'll accept what you can muster up now.

What's interesting about motivations is not just how tangled and mixed they can be, and how blind we can be to our own, but the way they can evolve. I thought of this during some recent conversations among people who are choosing to educate their children at home because they fear bomb threats and shootings.

The usual advice is: Don't make a decision like this out of fear! Make it for positive reasons! Make sure you know what you're getting into: don't just act on a momentary impulse.If you're going to do it, do it for the right reasons!

All good. And yet...it leaves something out. A person might begin homeschooling because she's fearful of bombs or disease or ideological bias but continue because she finds she enjoys her child's company once outside pressures have diminished. Or because the individual attention and freedom reveals a new interest or passion in the parent, or the child, or both. Or because people unexpectedly start to thrive.

Or someone might get married, or want to have a child, for imperfect reasons. For most of life's most momentous decisions--marriage and parenthood being two of the most obvious--it's crucial to try to realize what you're getting into, but it's also impossible really to know until you're in the thick of it.

The evolving doesn't necessarily move in such a positive direction, of course. But it can.

And it seems to me that if God, through His Church, has decided that He can work with imperfect motivation, we shouldn't be overly fearful of it in ourselves or in the people we live with.

We shouldn't be reckless, or settle for mediocrity. But neither should we let an interior perfectionism breed discouragement and despair.

---------------------------------

Image Credits:

Montgomery Clift in I Confess: Flickr

Black cat: Pxhere

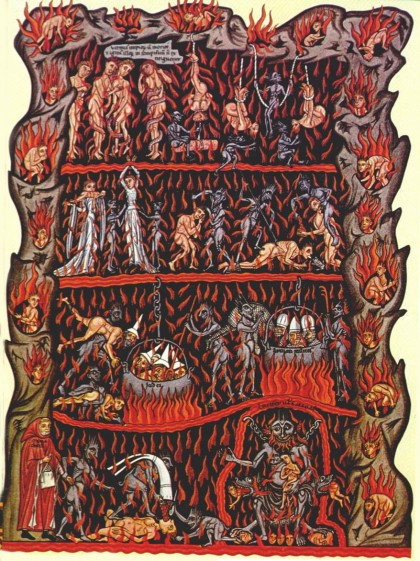

Hell: Wikipedia

Sea turtle skeleton: Gabriel Torres at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History

Good Shepherd: Max Pixel

Comments (4)

Kate Whittaker Cousino

Mar 8, 2018 3:50pm

Hmm. I think the difference is that desiring absolution is an objective good. There's virtually no condition under which going to confession is harmful, even if your intentions aren't pure. You can go to confession with no idea whether your contrition is really real and the worst that happens is that you make a bad confession and aren't absolved of your sins, and have to go back again.

Both your other examples involve making decisions involving other people, where the harm of wrong motivations can do more than annul the potential for good--it can actually lead to harmful outcomes. I'm not sure the comparison holds. Not that perfect intentions are necessary, but what proportion of right intentions to wrong intentions makes something a good choice?

Rhett Segall

Mar 9, 2018 8:14am

Got befuddled with the entry and redid it below!

Rhett Segall

Mar 9, 2018 8:19am

Purity of motivation was one of the key motives of the monastic ideals. "God alone"; "All for the glory of God". Yet this purity of intention is more a work of grace than asceticism. St. Bernard was once tempted to stop preaching because he saw that vanity was involved. But he didn't stop preaching and said "Satan, I didn't start preaching because of you and I'm not going to stop because of you!" I'm also reminded of the question Tevye asks Goldie in "Fiddler..." "Goldie, do you love me?" Do I love him? For twenty-five years I've lived with him Fought him, starved with him Twenty-five years my bed is his. If that's not love, what is?(Tevye)Then you love me?(Golde )I suppose I do(Tevye) And I suppose I love you too(Both)It doesn't change a thing But even so After twenty-five years It's nice to know.

I would differ with Goldie and Tevye-drawing their love to explicit awareness does change things.

Rhett Segall

Mar 9, 2018 8:23am

I agree with Kate that purity of motivation is intrinsic to the meaning of certain actions, such as marriage. Granted we may have mixed motives for the actions but in the case of marriage, love would have to be of the essence, at least in our culture or else its meaning is eviscerated.