A “Personal” Lord and Savior?

Devra Torres | Jan 2, 2013 | 4 cmts

“Have you accepted Jesus Christ as your personal Savior?”

What’s a personalist to make of this question?

It’s a familiar one to evangelicals—so familiar that you can easily gloss over what exactly it might mean. It’s also a question to which, since becoming a Catholic, I’ve learned a couple of preliminary comebacks:

First, of course, nowhere in the Bible does Christ say “Go out to all the nations and instruct them to accept me as their personal Savior.” It’s a relatively recent phrase, and its centrality to salvation—especially the way it displaces baptism—

is a modern invention.

Secondly, yes: the personal assent of the will, the free receptivity to the proffered gift, is indispensable. But there’s a problem with the way “personal” is used here—as synonymous with “individual”: it disregards the corporate aspect of the whole thing.

He is our personal savior, knows us by name, and doesn’t relate to us en masse—but He also saves us by incorporating us into His Mystical Body, the Church. Salvation is not an individualistic pursuit, not even for hermits..

Another possible interpretation of a “personal savior” is a savior with whom you have a comfortable, feelings-based relationship—that your religion is more than an impersonal, institutional bundle of rules, regulations, and rituals. Taken to extremes, this results in a make-it-up-as-you-go-along kind of faith.

Still, there’s a large grain of truth here that no personalist ought to overlook—Jesus Christ is a person. And what does that mean? It should give us pause no matter which denomination we call home.

Here’s the problem: We’ve already taken a giant step if we’ve gone from a theoretical belief in an all-powerful Prime Mover to a lively trust in someone who takes an interest in me, calls me by name, cares about my little problems, has a plan for me, and “gave Himself up for me.” (Gal. 2:20)

But it’s awfully easy to stall right there, oblivious to how one-sided and self-centered we’re being To awaken to the idea that He’s concerned for me and sees me as a person is key, but it’s only the first half of acknowledging Him as a Person. The second half is being concerned for Him, and seeing Him as somebody with an interior, with His own subjectivity, some reality beyond the aid, consolation, and trustworthiness He offers me.

That might seem nonsensical. How can anyone be concerned for Omnipotence? Can I be anxious about God’s wellbeing, as if He were a husband driving home on a snowy night

or a teenager fallen in with a bad crowd?

He has no need of anything. That’s Theology 101. What sense does it make to be considerate of God, take His feelings into account, do Him favors, or prepare Him a special treat? This is how we show love for fellow creatures. But it doesn’t seem to fit with God.

Yet we know that love demands reciprocity. In fact, as Bl. John Paul II put it, “this reciprocity is the very foundation, the soul of the Christian life.” It’s just as vital to acknowledge the subjectivity of the other when the other is God as it is when it’s anybody else. This reciprocity, or mutuality, isn’t exhausted by determining what the commandments are and responding correctly. He is a person, with a heart capable of joy and sorrow, at the mercy—but only because He so chooses—of our response.

For more serious treatment of this mystery, see Bl. John Paul’s Salvifici doloris, St. Thérèse, St. Faustina, and all kinds of writings on the Sacred Heart. It’s not a new idea, but if we ever put it into practice it would turn everything upside down.

Here are the passages that started me thinking along these lines, taken from my soon-to-be-published translation of Amor y Autoestima (“Love and Self-Esteem”) by Fr. Michel Esparza.

“Ordinarily,” observes Javier Echevarría, “we regard God as the source and content of our peace—which is true, but not the whole truth. We don’t tend to think, for example, that we too can console God and offer him a resting place. But this is how the saints have acted.”

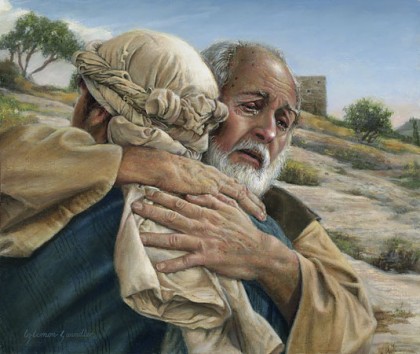

Fr. Esparza also draws on Henry Nouwen’s reflections on the Prodigal Son. We tend to identify with the runaway

or perhaps with his self-righteous elder brother.

But there’s another perspective: that of the Father.

Neither son seems mindful of his point of view—any more than we usually are of God's. Here’s Esparza, quoting Nouwen:

The elder brother…has failed to understand the love that drives his father’s continual concern for the wellbeing of both his sons—while each of them goes his own way, oblivious to the sorrow or joy he might be causing. The parable reveals not only the homeward path the prodigal son ought to take, but also the enormous pain his waywardness causes his father….“He is a God who rejoices at our affection and is pained by our coldness.” (emphasis mine)

So have you accepted Jesus Christ as your personal Savior?

And if so, are you sure you know what you’re getting into?

Comments (4)

Marilyn Prever

Jan 3, 2013 9:43am

Best yet!

Ima

Katie van Schaijik

Jan 3, 2013 9:57am

Devra, this beautiful and true, and an angle I have given too little attention to.

I was profoundly (and beneficially) influenced by evangelicals as a teen. And my consciousness of Jesus as "my personal Lord and Savior" has been all about the mystery of his love for me as an individual.

The more I've grown in my Catholicness, the more I've come to understand that corporate dimension too—the inter-subjectivity of our life of faith.

But I've thought far too little about this other element: the necessary reciprocity of all deep personal relations, and God's desire to be loved by us in his subjectivity.

Thank you.

Jules van Schaijik

Jan 3, 2013 1:25pm

Thanks for this wonderful reflection Devra.

Von Hildebrand, you may remember, has a lot to say about this in The Heart. It is especially, he thinks, through the Sacred Heart of Jesus, that we get a glimpse of the tender interiority of God. When Jesus pardon's the thief, for instance, this is not just a manifestation of His boundless mercy, but also of His joy "over the man who recognizes the divinity of the crucified Lord at the very moment in which the apostles believe that all their hope is buried." Or when Jesus repeatedly asks Peter "Do you love me?" He is not just making some moral or theological point. He also shows how much He longs to be loved.

It is a great point to dwell on, especially during this season in which we celebrate His incarnation.

Devra Torres

Jan 8, 2013 11:48am

I just saw that my responses to these comments never went up--my apologies!

Ima (Marilyn Prever, my mother, who taught me to write), thank you! Your opinion is very, very valuable to me. I think I get many of my ideas from slowly mulling over things you told me decades ago.

Katie: me too! I know I've run into the idea of "consoling the heart of Jesus" before, and the idea of thinking of His sadness in response to my sins as a motivation for sinning less, but it never made much of an impression on me. I assumed it was a variety of manipulation or sentimentality, a means of making me feel bad about things I was probably going to do anyway. I thought I was responding rationally to the idea that He's omnipotent, so how could He be affected by any action of mine? But it was more like a failure to take His personhood seriously.

Jules, yes, I need to take another good close look at The Heart!