A Personalist Universe

Devra Torres | Sep 18, 2012 | 8 cmts

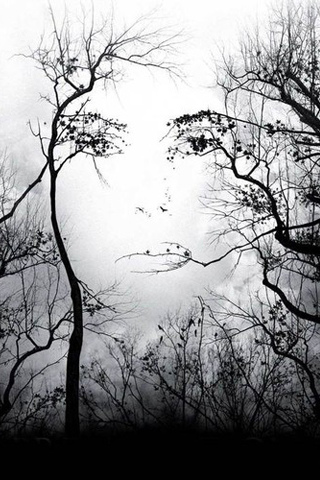

The other day, my husband and I were taking a walk. We looked up and saw this:

Here are some questions we didn’t ask:

- What could have produced that unusual cloud formation?

- See how the hand of unguided, purposeless coincidence caused those letters to form in the sky?

No, we ruled coincidence out. In fact, there were three separate things the letters told us.

- First, they were designed. I can’t theoretically disprove that just the right combination of air currents, evaporation and condensation might have produced them. But surely it’s the least plausible explanation of all.

(Now, if you go to The Cloud Appreciation Society’s website--a delightful place to go in any case--there’s a whole category called Clouds That Look Like Things. Some are striking, like this horse:

But none point unmistakably to the deliberate action of a designer.)

- Second (the letters tell us),the designer is rational. Not only were the shapes non-random, they conveyed a meaning. They were symbolic.

- Third, the designer is a person who had us in mind. There was a message built into the contrails. In this case, it was the prosaic wish that U of Michigan should win the game. But still: an interpersonal message, conveying pride and encouragement.

Now, everybody knows that skywriting is created on purpose, conveys a message, and is designed with an observer in mind. The same is true of the physical universe.

I'm not setting out here to prove the existence of a personal God or to demonstrate which method He did or didn't use to produce the universe.

I'll resist the temptation to analyze just how well old-time Darwinism and its offshoots hold up once the sediment of ideology and wishful thinking is sifted away.

(If the subject nterests you, though, you might like Darwin’s Black Box, by Michael Behe and Darwin on Trial, by Phillip E. Johnson.)

What I want to address is what a difference it makes whether you believe the universe is designed by a Person, with persons in mind--in other words, that this is a personalist universe.

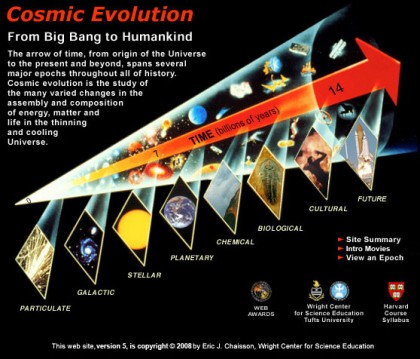

If you believe it’s not, you might be inclined to feel, like the late Carl Sagan, that

“we live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe.”

You might also be inclined to proclaim bravely:

Leaving aside whether Sagan's religion-delusion equivalency is convincing, he and others like him succeeded wildly at something else: insinuating the assumption that if a belief is satisfying and reassuring, then it's likely to be a delusion.

If you really think that the ultimate reality is pointless randomness,

you’re operating with a very different mental background than if you believe in a Creation designed by a Person who takes an interest in you—that man is "the only creature on earth that God has willed for its own sake," as the Catechism puts it.

But as David Mills points out in this month’s issue of First Things: Wait a minute. When Sagan calls our planet insignificant—insignificant to whom?

And "forgotten"? Forgotten by whom?

Who is this subject who bestows “significance” on the larger, more impressive planets but is prone to “forgetfulness” about the smaller, less centrally located ones?

Even to say that our star is “lost” in its backwater galaxy hints either that Somebody misplaced it or else that the star itself is feeling deserted or neglected.

How did all that personhood sneak back in there?

People who disbelieve in a personal Creator have a strange tendency to slip into just this kind of talk. They tend to speak of “Nature” so anthropomorphically that you start to see her as a very clever, resourceful character who has her reasons for arranging things as she does.

I noticed the same tendency in a National Geographic video about pollination and ecosystems I used for my kids' science class once, and in lots of popular "green" writing for both children and adults. Perhaps it's for propaganda's sake—the advantages of instilling a facsimile of religious fervor are clear—but it seems to slip in even when no one's intending it.

It’s powerfully reminiscent of the way absolutism sneaks into attempted defenses of relativism. ("It's absolutely true that everything's relative! Oh--wait a minute...") Something about the universe seems to hearken back to personhood.

You could dismiss it as a persistent quirk of the human mind. Or you could show logically that something higher (a person) doesn't come from something lower (an impersonal process). But maybe it's simpler. Like the message in the skies over the U of M stadium the other day, maybe this one would be obvious, too, if we had eyes to see it.

Comments (8)

Sapperdepitjes

Sep 19, 2012 3:47am

Philosopher Jean Guitton to former President and socialist François Mitterrand on his deathbed: "Monsieur le Président, il faut choisir entre l'absurde et le mystère." — Mr. President, one has to choose between the absurd and mystery.

Marie Reimers

Sep 19, 2012 8:40am

I read Walker Percy's Alone in the Universe - The Last Self-Help Book, last summer. It was an excellent and fun read, making many of the same points. Good essay, Dev.

Katie van Schaijik

Sep 19, 2012 8:50am

I'll never forget Josef Seifert's critique of "random mutation". He invited us students to imagine the parts of a Volkswagon strewn throughout a garage. And then, thanks to a violent earthquake, they fly together and form a fully operating car.

Tim Cronin

Sep 19, 2012 4:13pm

Saving the Appearances: Creation's Gift to the Sciences

We should make our arguments for Creation from Existence and Essence. From the whole things of nature intinsically related to the whole universe.

Darwin's invisible hand that is natural selection doesn't have a way to correlate the parts to the whole in his mechanistic ontology. A mechanistic ontology doesn't make sense. Likewise our arguments should not put forth an external relation of objects in nature mechanically connected. Instead it should come from the mystery of existence which we share. It should question why there is something rather than nothing.

vickie teetor

Sep 20, 2012 4:11pm

Thanks for my weekly dose of Devra!!

Devra Torres

Sep 20, 2012 4:32pm

Thank you, everyone! I'm seven hours from a translation deadline and hope to have more to say after that!

Devra Torres

Sep 22, 2012 6:05pm

Sapperdepitjes: Yes, and the absurd tries to pass itself off as the rational, the objective...

Marie, thank you for reminding me of that book--I'll have to read it again. His Love in the Ruins is a good one, too.

Katie: yes, when I first got interested in the evolution/intelligent design discussion, I'd keep running into claims that turned out to be, basically, the Volkswagen parts-to-car scenario, and I'd think, that can't be right--they can't really be claiming that--but they were. It was a lot like when our old Protestant friends would read the Bible and come up with the most anti-common sense interpretations (all the while claiming to just be accepting the textual evidence), and my parents realized: they're not so much interested in what the Bible actually says; they're more interested in making sure they don't believe what the Catholics believe. It's like the claim that there's an infinite number of parallel universes: it's not that there's any evidence for it; it just enables them to avoid believing that our own is something special, like the Christians believe.

Devra Torres

Sep 22, 2012 6:10pm

Tim, I'll have to take a look at your link and do it more justice after I get some soup off the stove and get ready to take my son (speaking of cosmology) to go see an astronaut at a planetarium for his birthday!

As far as I understand it, the argument from irreducible complexity is related to the issue of correlation--and, yes, "Why is there something instead of nothing?"--of course it's not a properly scientific question, but proponents of non-directed evolution cross that line themselves when they try to move from "that's not our department" to "there is no Why."