The personalist view of marriage is not anti-modern

Katie van Schaijik | Nov 27, 2011

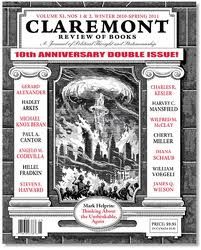

I find in the latest issue of the Claremont Review of Books a review of a book titled Family Politics: The Idea of Marriage in Modern Political Thought, by Scott Yenor. According to the review, it is "a philosophic reflection on the troubles of the modern family"—a critique of the post-Enlightenment view of marriage in light of John Paul II's teachings on the subject.

I find in the latest issue of the Claremont Review of Books a review of a book titled Family Politics: The Idea of Marriage in Modern Political Thought, by Scott Yenor. According to the review, it is "a philosophic reflection on the troubles of the modern family"—a critique of the post-Enlightenment view of marriage in light of John Paul II's teachings on the subject.

Being an intuitive rather than a methodical thinker, I am, I fear, rather prone to snap judgments. Nor is it fair to evaluate a book by a single review. But, with those caveats in mind, let me say that this review inclines me to think I won't much care for the book. I suspect it of being marred by two bad tendencies often found in those who consider themselves proponents and teachers of John Paul II's thought:

- a reactionary anti-modernism, and

- a damaging misunderstanding of the personalist notion of autonomy.

The author of the review, Dorothea Israel Wolfson, compliments the book for its "thorough and deep" treatment of the subject, while criticizing it for being perhaps "too counter-cultural, as it were, to be effective. One wonders how much appeal these teachings can have beyond already committed Catholics." Her point strikes me as valid and not unrelated to mine. Let me try to explain.

I am entirely with Yenor in deploring a view of marriage that reduces its essence to a contract between consenting adults. I agree, too, with his contention that "modern political thought has had the effect, and in many cases the intention, of undermining the natural and conventional foundations of the family." But here is my objection: he seems to view "modern thought" too exclusively from the point of view of its defects, without a corresponding appreciation for its valid aims and real achievements. He treats modernity as if it were nothing but "a bundle of errors to be refuted" (as I remember Dr. Crosby once putting it.) Here is one example.

Yenor points out (according this review) that in the 19th century John Stuart Mill called for the equality of the sexes in marriage. Mill thought that the progress of liberty in the public sphere was impeded by "the tyranny of men over women" in the private sphere of marriage. He therefore advocated what he called "assimilative marriage" in which "husbands and wives are true friends and equals." Yenor critiques Mill for failing to take account of children:

Mill ignores the kids in order to propound an alluring promise of spousal friendship—the idea that husbands and wives will share the same experiences and the hope that they will be soul mates.

I'm all in favor of a view of marriage that takes due account of its fundamental orientation toward children. But I am left wondering whether Yenor means to suggest that husbands and wives are not equals? Should they abandon the notion of being soulmates? Does he think Mill was wrong to oppose the tyranny of men over women in marriage? Or would he agree that there have been real gains through the modern struggle for sexual equality? If so, it doesn’t come through in this review. One gets rather the impression that Yenor is using John Paul’s work for an un-John Paulike purpose: namely, to condemn the modern world.

Later in the review, we find that Yenor evidently treats "self-giving love" as the contrary opposite of "individual autonomy"—as if autonomy were synonmous with egotism and self-seeking. Yet, in the personalist understanding, individual autonomy has nothing to do with selfishness. On the contrary, far from being inimical to love, it is the indispensable ground of love. One cannot give what one does not have. I cannot give myself properly in love unless I realize fully my own autonomy. Without it, my self-giving is all too likely to be a dysfunctional, co-dependent self-squandering—a counterfeit of love.

On this point, let me draw attention to a section of our “Personalist manifesto” recently highlighted by member Teresa over in the member forum:

[Our concept of Personalism] rejects the ethical altruism which asserts the claims of others so forcefully that any interest in our own happiness is made to appear as selfish; against this it affirms that the moral subject is also a person and thus also one who may not simply be used, or let himself be used, for the good of others.

It is not too much to say that a right appropriation of the modern notion of individual autonomy—one that interprets it in due relation to other truths, including truths like "It is not good for man to be alone" and "a person is called to give himself in love to others"—clarifies, enriches and deepens our understanding of the mystery of love, and hence our ability to participate in it.

Let me return to the reviewer's concern that Yenor's book may be "too counter cultural" to be effective. One of the reasons John Paul was able to be such a profoundly influential Pope and philosopher is surely his remarkable, sympathetic openness to the modern world. Unlike many of his would-be followers, he did not simply reject modernity wholesale and re-assert Tradition in opposition to it. Rather, he encountered it thoughtfully, entered sympathetically into its legitimate concerns and aspirations, sifted the wheat from the chaffe, appropriated what he found to be good and true, and brought it into fruitful contact with the living Tradition he knew and loved so well.

If we want to be his disciples, we should do the same.