Worse than a Nanny State

Devra Torres | Apr 18, 2013 | 5 cmts

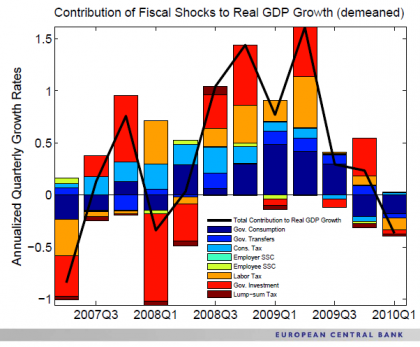

To say that fiscal policy is not my forte is—let’s put it nicely— an understatement. (In fact, I chose this graph because it was so pretty.) But there is an important personalist point to be made about it anyway, and maybe I can express it in a way that other liberal-arts types can understand.

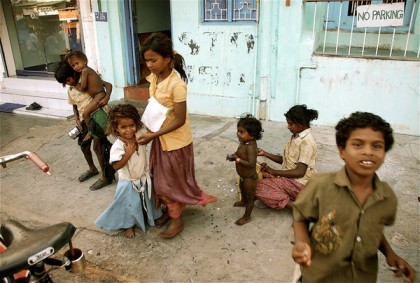

Many labor under a perceived conflict between taking seriously the Church’s concern for the poor, on the one hand, and treasuring the rights of the individual, including the taxpayer and entrepreneur, on the other. The “social justice Catholics” object to neglecting the poor in the name of the economic freedoms of people who could help them. Small-government advocates object to a state that curtails their liberties and confiscates their hard-earned income to fund bureaucracies to help the poor. So should we choose up sides, with the dignity of the poor pitted against the rights of the taxpayer?

But there’s a much deeper point at issue. Here’s a quote from the no-longer-little-known Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio:

We cannot truly respond to the challenge of eradicating poverty and exclusion if the poor remain objects targeted by the paternalistic and interventionist action of the state and other organizations and not subjects, where state and society generate the social conditions that promote and safeguard their rights and enable them to be builders of their own destiny.

There you have it: combatting poverty and exclusion without forfeiting the “building of one’s own destiny.” The “paternalistic and interventionist” state accomplishes neither.

The trouble with being paternalistic and interventionist—in the extreme case, totalitarian—is that even if it’s well intentioned (which is debatable) and even if it produces good effects (as it sometimes does) it’s not approaching us as persons.

Even if we’re recipients of its “beneficence”—whether by accepting taxpayer-funded highways

or tuition assistance, or food stamps—that’s not the point. It’s not whether immigrants, or poor people, or students, should be objects of the largesse of a condescending and intrusive institution. The pertinent question is not whether it selects you or someone else to receive its benefits or penalties, but whether it gives you room to freely develop your personhood, as a subject, making choices that have moral and economic consequences.

This is no brief for anarchy or even libertarianism. The state has a role to play. It can nourish structures that allow the person to flourish as a subject. It can make sure there’s a safety net, too

(though it doesn’t help to arrange the system so that the federal safety net is the default option for everybody except a few politicians). But that doesn’t mean the government ought to usurp the person’s authority, replacing his own decision-making center.

So when we see politicians wanting to distribute Plan B to children or IVF to same-sex couples, or instructing our military to regard Catholics as potential terrorists, or outlawing Big Gulps, it’s more than a problem of whose money gets given to whom, or whose moral principles get trampled on in favor of whose.

Our “dialogue” should not degenerate into a contest between those who want the poor to get help and those who think that their poverty is proof enough that they don’t deserve it. Nobody should have to pick sides between thinking the state should care for the poor and thinking the poor shouldn’t get care.

This is not a theoretical problem. What some call “conservatism” has become a simplistic battle between “makers” and “takers,” with the former keeping a firm grip on their wallets and fending off the latter, whether those be individuals or whole countries.

For a worldview worth taking more seriously, here’s Cardinal Bergoglio quoting Bl. John Paul:

In the encyclical Centesimus annus, John Paul II warned of the need to "abandon a mentality in which the underprivileged--people and nations--are considered a burden, or annoying inconveniences eager to consume what others have produced." "The poor,” he writes, “demand the right to share in the joy of material goods and to make fruitful their capacity for work, thus creating a more just and prosperous world for all."

Maybe this could be the real common ground: if we stop focusing on whether or not the beneficiaries of government (i.e., taxpayer-funded) largesse are worthy of it, and start focusing on insisting that everyone be treated as a subject, not an object.

This is not a new argument. People talk about the nanny state, but it’s not so much that a “paternalistic and interventionist” government treats us like children—developing persons who need help in learning to use their own freedom, judgment, and subjectivity. Rather, it treats us like inanimate objects. A good nanny develops her charges’ ability to take initiative; she doesn’t just tyrannically make all their decisions for them, preparing them to be children forever.

Now, in the spirit of Pope Francis, a very practical man, we should ask: What would a country look like that treated its people as subjects, not objects? How would that translate into fiscal policy and budget decisions? I welcome comments from people with more expertise (or anybody else with an interest in the conversation).

Comments (5)

Katie van Schaijik

Apr 19, 2013 7:39am

Since the election of Pope Francis, I've been working on an article trying to clarify the difference between the Catholic sense of social justice and the leftist sense of social justice. That first quote about the problem of paternalism is just what I want. Could you give a reference?

Another, longer-term project of mine is an article on the problem of patneralism.

Devra Torres

Apr 19, 2013 9:14am

That sounds like a much-needed article! It's complicated, and of course many people have addressed the subject, but even what's already been said doesn't seem to have trickled down to the non-specialists. I know there's lots to be said about the principle of subsidiarity, and clarifying how it's not at odds with solidarity. But I was struck by how personalist the talk of subjects and objects was. It's from an address at the Inaugural Conference at a seminar on "social debt" in Buenos Aires on Sept. 30, 2008. This is a preliminary translation. The whole thing will appear (pray that it's soon!) in a book put out by Scepter called (tentatively) Encountering Christ. It's a collection of homilies, addresses and letters of then-Cardinal Bergoglio.

I wanted to write about this, too, because of the increasingly simplistic and nasty discussion of the subject I've been hearing lately on the radio. There's a good case to be made about how creeping totalitarianism serves neither poor people's dignity nor their finances, nor anybody's, but what you hear on the popular level is less of that and more contempt for "takers."

Katie van Schaijik

Apr 19, 2013 11:05am

I'm jealous of people who can read Spanish.

I'm also grateful for competent translators. Looking forward to the book!

About the subject/object point, you're exactly right that this is a key difference between the leftist view of social justice, which treats persons as objects in a giant social scheme, and the Christian idea of social justice, which has to do with our intersubjectivity.

Leftist social justices subordinates the individual to the collective. Catholic social justice is grounded in the dignity of the person, but attentive to its "communitarian dimension."

Sam Roeble

Apr 26, 2013 3:08pm

all in all, I think the key to charitable work is relationship. That is to say, one cannot truly 'work with the poor' unless one has a relationship with a 'poor' person.

Unfortunately in the modern world, that means that some familiarity with substance abuse treatment is a requirement for working w/ the poor (in developed countries). The Americas suffer from 'isolationist poverty' due largely to drug use--whereas 3rd world countries have more of a communal poverty.

That makes things very difficult--because ultimately, the eradication of poverty is closely tied to the eradication of addiction.

My hope is that Pope Francis will address this issue in Rio De Janiero for WYD because it particularly effects youth...

Devra Torres

Apr 26, 2013 3:15pm

Samwise, that's a good point. I think a big problem with poverty programs set up by politicians is that so few of them have ever been poor or ever socialize with people who are, that at best they're ignorant, at worst speaking from a perspective of contempt.

From some references in the book. it seems to me that Pope Francis does have some experience with the subject of drugs. Argentina is pretty "European" for South America, but he talks about the drug problems in the poorer outskirts of Buenos Aires like someone with first-hand knowledge.

The book will be called Encountering Christ. I can't wait for everyone to read it!